Dark Fiber—an Archaeology of the Dot-Com Bubble

The fiber laid in the 1990s built enduring routes for digital power and profit

In the late 1990s, the dot-com boom was defined by euphoria. Stock tickers surged as day traders chased internet IPOs, venture capitalists bankrolled websites selling everything from books to pet food, and Wired magazine cast the era as the dawn of a limitless digital frontier. But behind the exuberance lay something more durable than speculative startups—the laying of a physical skeleton for the digital age. While Wall Street inflated valuations, crews from Qwest Communications threaded hair-thin strands of glass into conduits along the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railway outside Denver, joining similar projects that stitched hundreds of thousands of miles of fiber across the continent. Each strand was capable of carrying millions of simultaneous conversations, embedding the future of connectivity into the industrial corridors of an older America.

When most people recall the dot-com bubble, they think of speculative websites, IPO frenzies, and start-ups with no profits but sky-high valuations. Less remembered is that it was also built into the ground, a frenzied effort to rewire the nation’s infrastructure with glass. At the time, Wired captured the paradox of this overbuilding with a sharp observation:

The silicon economy obeys the law that supply creates demand. Too bad it’s not true for fiber. It’s hard to remember, as the tech world drowns in a sea of glass—the megamiles of excess fiber-optic cable dragging down the telecom sector—that glut was supposed to be a good thing. ‘Supply creates demand’ was the rallying cry of the semiconductor economy: Carpet the world with cheap technology, and clever hands will put it to work in a thousand ways never before imagined, giving rise to new markets and new demand. Want to carry your entire music collection in your pocket? Sure! Now how about all the music ever recorded? You bet. Moore’s law boiled down to one word: more. The more you have, the more you use. While traditional economics are driven by scarcity, the world created by the microchip is one of abundance.

That tension between speculative optimism and infrastructural overcapacity defined the bubble’s legacy. And it lingers today, as some analysts warn that the current AI data center boom may echo the 1990s “fiber glut”—with massive overbuilding, uncertain demand, and bubble risks despite the prevailing faith in long-term growth.

Deregulating the Backbone

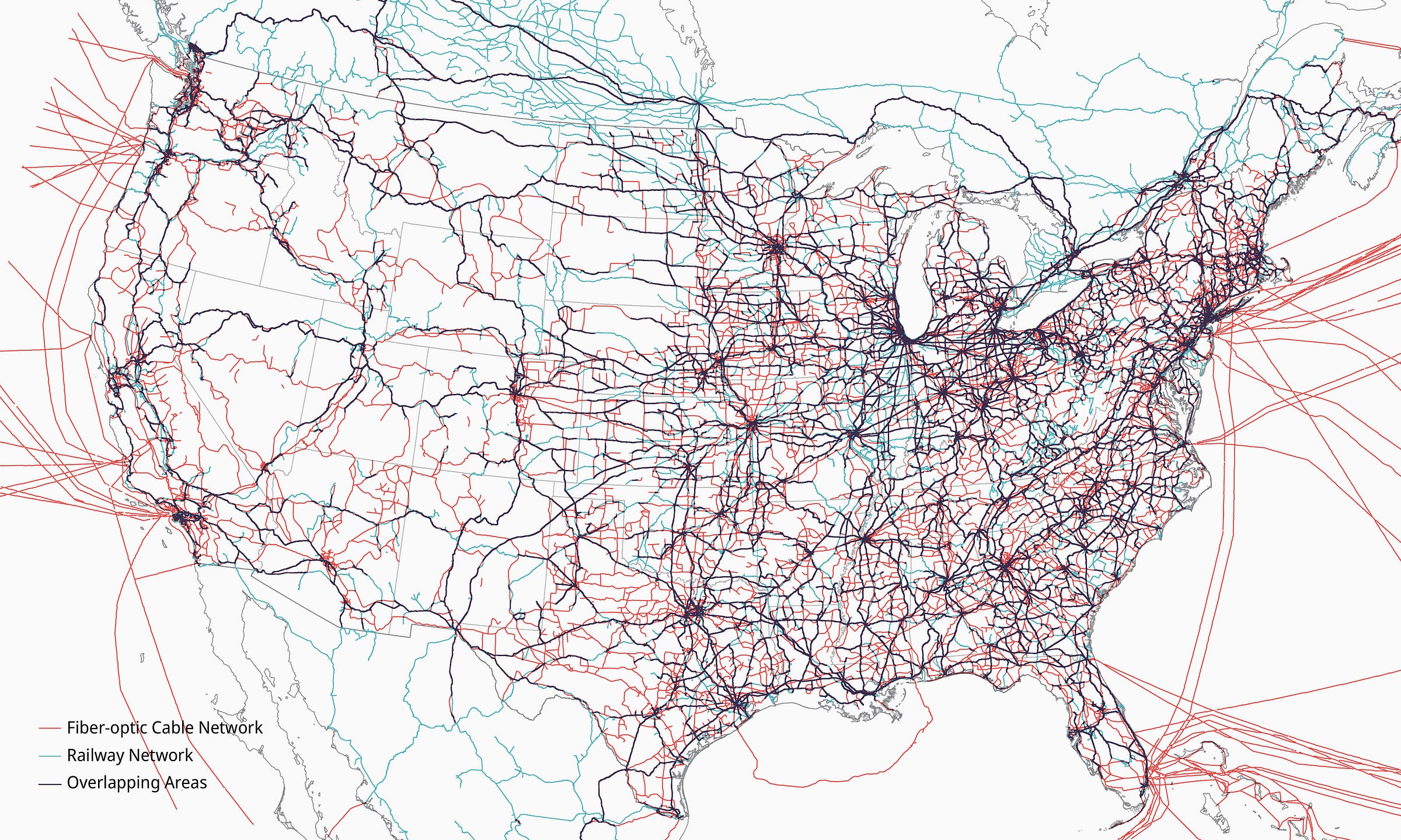

The “internet economy” was, in practice, a massive archaeological project—turning the buried infrastructure of industrial capitalism into the nervous system of digital capitalism. The bubble had a geography, mapped onto rights-of-way assembled generations before anyone had dreamed of the internet.

The real wave of excavation began with the Telecommunications Act of 1996, legislation that promised to dismantle entrenched monopolies in local and long-distance telephone service while opening the way for commercialization of NSFNET and the wider Internet backbone. Backed by a Republican congressional majority and a corporate sector eager for new markets, the Act drew ideological support from the mid-1990s rhetoric of the “knowledge age.” A 1994 manifesto titled Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age captured the mood, declaring: “The central event of the 20th century is the overthrow of matter. … The powers of mind are everywhere ascendant over the brute force of things.”1

Two years later, on the very day the Act passed, John Perry Barlow issued his now-famous Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace at the World Economic Forum in Davos.2 Barlow’s declaration echoed the frontier language of the moment, envisioning cyberspace as a realm beyond government regulation and the legal frameworks “based on matter,” a space that claimed to transcend the material world altogether.

Beneath the rhetoric, industry insiders were more cleareyed on the “matter.” An article in Network World explained the reality of the situation at the time, “[u]ltimately, the Internet will boil down to a few big providers with bilateral agreements on how to interoperate, service and support one another’s networks.”3 Yet, for many others immersed in the zeitgeist of cyberspace, it seemed that anyone with enough capital could become a carrier.

Wall Street responded to the Act by financing dozens of new telecommunications companies, each racing to string fiber across the landscape before their rivals could claim the choicest routes. The logic seemed unassailable. If every website, email, and eventually video would rely on moving bits of light through glass, then whoever controlled the most glass would win. Equipment vendors like Lucent and Nortel sweetened the stakes with generous vendor financing—essentially lending money to carriers so they could buy more gear. Bond markets and equity investors poured in billions, convinced that internet traffic was set to explode exponentially.

What emerged was a peculiar marriage of old and new America. Qwest, which had grown out of a railroad construction company, raced to string fiber along rail corridors stretching from Denver to Seattle. Williams Communications, born from a natural gas pipeline firm, launched WilTel to thread cables through pipeline rights-of-way across the South and Midwest. Even the Southern Pacific Railroad’s telecommunications unit evolved into Sprint (Southern Pacific Communications Company), transforming steel rails into information superhighways.

Already in 1995, Bay Area Rapid Transit struck an agreement with MFS WorldCom to install fiber through BART's tunnels beneath San Francisco Bay—valued around $40 million. The negotiations, conducted in fluorescent-lit conference rooms overlooking the Bay, would have seemed surreal to the nineteenth-century engineers who first imagined moving people through underwater tubes. Today, BART still licenses strands and touts connections to 40+ data centers, demonstrating how an “information superhighway” trope hardened into a durable revenue line—and a regional connectivity scaffold.

Overlapping Fiber-optic Cable Network and Railway Network in 2025

The Mathematics of Delusion

This continental rewiring was also justified by another powerful myth—that internet traffic was doubling every 90 days. The claim spread through analyst reports, earnings calls, and investor presentations like a particularly virulent meme. If true, it meant that demand was growing exponentially, far outpacing any conceivable supply, and that every new trench of fiber would soon pay for itself many times over.

But the mathematics were fiction. Network researchers like Andrew Odlyzko (at AT&T), looking at actual traffic data, found that U.S. backbone traffic was doubling roughly once a year—rapid growth, certainly, but nowhere near the purported 90-day cycle. Meanwhile, advances in fiber technology were making each strand exponentially more powerful. Dense wavelength-division multiplexing allowed dozens of signals to travel simultaneously down the same line at different wavelengths of light, like multiple conversations happening in different colors.

While demand doubled annually, supply expanded tenfold or more. Carriers buried the discrepancy under layers of creative accounting that would have impressed medieval alchemists. They sold “indefeasible rights of use”—essentially decades-long leases on fiber capacity—and booked the entire value immediately as revenue. They engaged in elaborate “capacity swaps,” trading bandwidth with competitors and treating each exchange as a sale, manufacturing revenue from thin air.

Companies like Global Crossing built themselves into financial giants through such sleight of hand, reporting explosive growth quarters while laying ever more fiber through an already saturated landscape. The executives knew they were building far ahead of demand, but the stock market rewarded growth above all else, and growth meant more fiber, more routes, more light racing through more glass.

The Unraveling

When the illusion finally collapsed, thousands of miles of fiber remained “dark,” unused. Global Crossing declared bankruptcy in 2002, leaving behind $12.4 billion in debt and thousands of miles of dark fiber. WorldCom followed in what became the largest accounting fraud in U.S. history, its executives having inflated revenues through the same capacity-swap schemes that had fooled Wall Street for years. By 2004, wholesale long-haul prices had fallen roughly 55% year-over-year in the U.S., with analysts estimating only about one-tenth of installed fiber was actually “lit.”

The human cost was immediate. Hundreds of thousands of jobs vanished, pension funds evaporated, and entire communities built around telecom hubs found themselves stranded. But the fiber itself remained buried, waiting in the dark like some technological archaeological deposit. What emerged from the wreckage was not emptiness but a new geography of connectivity. The crash didn’t erase the networks; it reorganized them, concentrating power in unexpected places while creating opportunities elsewhere.

Legal battles also reshaped the map. After the bubble burst, landowners filed class-action suits against carriers who had strung fiber along railroad rights-of-way, claiming the installations exceeded the scope of century-old easements. Courtrooms from Montana to Georgia heard testimony about the original intent of nineteenth-century railroad grants, with lawyers arguing over whether "telegraph and telephone" rights covered fiber-optic cables. By the mid-2000s, companies like Sprint, Qwest, and Level 3 were paying out hundreds of millions in settlements, but the legal victories effectively legitimized thousands of miles of routes, cementing the corridors of national internet backbones.

Meanwhile, a few urban buildings became irreplaceable nerve centers. One Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, once a generic downtown office tower, transformed into the primary connection point for trans-Pacific internet traffic. Walking through its floors today feels like entering the circulatory system of the global internet—endless racks of equipment, cables snaking between floors, the constant hum of cooling systems maintaining the temperature for machines that never sleep. In 2013, the building sold for $437 million, its value derived not from square footage but from its position at the center of digital trade routes.

Similar transformations occurred across the continent. New York's 60 Hudson Street, a 1930s Art Deco monument to the telegraph age, reinvented itself as a global internet hub. Google acquired 111 Eighth Avenue—once a freight terminal for the city's garment district—for $1.8 billion in 2010, converting it into a fortress of servers and switches.

From Glut to Cloud

It’s tempting to moralize the bubble as pure waste. Yet the spatial outcome complicates that view. A chunk of today’s digital economy sits on infrastructure financed by yesterday’s exuberance, regulated by yesterday’s scandals, and optimized by today’s platforms. The bubble “mispriced risk,” but it also front-loaded an intercity network whose replacement cost would be politically and fiscally daunting now. In practical terms, the crash was a transfer mechanism—from speculative carriers to durable holders (carriers, clouds, and public networks) that could squeeze more utility from the same glass.

The fiber glut also created unexpected opportunities for public institutions. Universities and state networks, suddenly able to acquire dark fiber at fire-sale prices, built research backbones that would have been unimaginable during the bubble years. Ohio's OARnet purchased fiber in 2001 and 2002, lighting a statewide network by 2004 that connected rural hospitals to urban medical centers and linked small colleges to supercomputing resources. Internet2's FiberCo signed deals with Level 3 in 2003 for thousands of route-miles of dark fiber, enabling a new generation of research collaborations spanning continents.

Perhaps the most profound consequence was how cheap long-haul capacity enabled an entirely new model of computing. With bandwidth costs in freefall, technology companies could locate massive data centers wherever land and power were cheapest, as long as they could connect to the fiber backbone.

Google's decision to build one of its first hyperscale data centers in The Dalles, Oregon exemplified this new geography. The town of 15,000, situated along the Columbia River, combined abundant hydroelectric power with access to multiple fiber routes threading through the Columbia River Gorge. What had once been aluminum smelting territory—industries that relocated to chase cheap electricity—became the foundation of cloud computing. See my article on this here:

Northern Virginia's “Data Center Alley” grew even more dramatically, transforming former tobacco fields in Ashburn and Sterling into the world’s largest concentration of server farms. The region’s advantage wasn't natural resources but historical accident with some of the earliest internet exchange points and a dense concentration of long-haul cables converging on the nation’s capital.

As predicted, the survivors of the telecom crash had consolidated into a few large networks by the 2010s, eliminating redundant routes and rationalizing the backbone. Meanwhile, hyperscale companies like Google, Microsoft, and Facebook began building their own long-haul and subsea cables, taking advantage of surplus capacity while bypassing traditional carriers entirely. The immense wealth and power of these companies built on the backbone of a prior industrial era.

The Maps that Infrastructure Bubbles Make

The dot-com bubble is often remembered as a cautionary tale about irrational exuberance and failed startups, but its most enduring legacy lies buried under railroad beds and highway shoulders across the continent. Three patterns continue to shape digital geography and the new infrastructural order. First, the corridors of industrial capitalism became the arteries of digital capitalism. Railroad rights-of-way and pipeline easements offered the fastest paths to lay fiber, and even after bankruptcies and lawsuits, those routes remain the backbone of continental networks. Second, a handful of urban buildings became irreplaceable switching points where networks connect and traffic flows. The crash eliminated many carriers but reinforced the critical importance of neutral interconnection facilities. Third, the dramatic oversupply created lasting opportunities for public institutions and eventually hyperscale companies to acquire infrastructure at prices that would never again be available.

The bubble didn't just misprice internet stocks—it restructured territory itself. Capital evaporated, but glass remained in the ground. That glass, threaded through the landscape during a few years of technological optimism and financial excess, continues to channel the uneven and unequal flows of our digital age. As the AI boom accelerates, we should look not only at valuations but at the infrastructures being laid down—data centers, energy systems, water pipelines—because these will sketch the next territorial outlines long after the hype has passed. Bubbles burst, but the infrastructures they leave behind endure, shaping power across and over many landscapes. What sort of map will be left behind in the next few years?

References

This manifesto was authored by prominent technologists and neoliberals: Esther Dyson, former Wall Street analyst and member of Clinton's National Information Infrastructure Advisory Council; George Gilder, supply-side economics advocate and author of Wealth and Poverty; George Keyworth, Reagan’s Science Adviser; and Alvin Toffler, futurist and author of The Third Wave, which promoted the post-industrial society thesis. See Dyson, Esther, George Gilder, George Keyworth, and Alvin Toffler. 1994. “Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age.” Future Insight. http://www.pff.org/issues-pubs/futureinsights/fi1.2magnacarta.html.

Barlow, John Perry. 1996. “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence.

Cooney, Michael, Adam Gaffin, and Ellen Messmer. 1995. “Internet Surge Strains Already Shaky Infrastructure: Who Will Manage the ’Net’s Commercialization?” Network World 12 (14): 1; 67.

For more reading on these events and their enduring legacy, I recommend:

McChesney, Robert W. 1999. Rich Media, Poor Democracy: Communication Politics in Dubious Times. Baltimore, MD: University of Illinois Press.

Aufderheide, Patricia. 1999. Communications Policy and the Public Interest: The Telecommunications Act of 1996. Guilford Press.

Kesan, J., and Rajiv C. Shah. 2001. “Fool Us Once Shame on You - Fool Us Twice Shame on Us: What We Can Learn from the Privatizations of the Internet Backbone Network and the Domain Name System.” Cyberspace Law eJournal, February.

Turner, Fred. 2010. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. University of Chicago Press.

Schiller, Dan. 2014. Digital Depression : Information Technology and Economic Crisis. Geopolitics of Information. Baltimore, MD: University of Illinois Press.

Excellent piece, very informative.

Capitalism is defined by booms and busts. However, I do think the dot.com and now the AI booms prove that humans learn some things from the past. The railroad boom after the civil war had a similar dynamic in overbuilding the supply but a lot of those routes were poorly built and made no sense for rail networks. Hence, a lot of those tracks were removed or needed to be redone. Dot.com was built on bad business models/assumptions but atleast the infrastructure didn’t need to be redone. AI is now being led by the strongest companies in world history with massive investments in infrastructure with the demand for that infrastructure still outpacing the supply. This can be seen in pre-leasing of new developments by both co-location and neocloud providers. Makes one wonder how early we are in the boom phase during this cycle