Semiconductors, Sprawl, and the Making of Arizona’s Techno-State

From Cold War defense plants to CHIPS subsidies, how speculative growth politics now serve global chip manufacturing

Arizona likes to tell a simple story about itself—a desert that willed a high-tech future out of dust and sunshine. Semiconductor fabs rise out of the Sonoran scrub, data lines pulse under the sand, and articles now rightly point out that “Arizona is at the center of two of the biggest technological transformations of the decade: the semiconductor boom and the rapid rise of AI-driven data centers.” Until recently, there has been a reassuring narrative in the air—that after decades of offshoring and financial crisis, the state is finally building things again.

Behind the headlines about the CHIPS and Science Act, record foreign investment, and an AI data center boom is a different kind of project. A massive restructuring of land, water, and public institutions to absorb risk on behalf of some of the most powerful firms on earth. What is being built in Arizona is not just a cluster of fabs (and data centers). It is a way of governing territory that relies on subnational agencies, utilities, universities, and developers to make the desert “investable” for capital that can leave as quickly as it arrived. I will focus solely on semiconductor development and leave data centers for another time.

This essay offers a brief introduction to my recent research, including my open-access article: “Techno-Statecraft and Industrial Strategy: Semiconductor Development in Arizona,” published in Contemporary Social Science.

Part of the argument I want to make is that what is often celebrated (or derided) as the “return” of U.S. industrial policy looks, on the ground, less like a centralized plan and more like a fragmented (but coordinated) campaign to remake particular places as platforms for high-tech accumulation. Arizona is a pretty good example of this model par excellence. To understand what is at stake, we have to situate today’s AI and semiconductor boom within the state’s longer history of speculative growth, and then watch how that history is being folded into the day-to-day work of building fabs, pipelines, and roads for companies like Intel and TSMC.

Silicon Desert stories

The national story starts in Washington. In 2022, Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, promising more than $50 billion in subsidies and tax credits to re-shore semiconductor manufacturing and reduce dependence on East Asian supply chains. The law is routinely framed as a sovereign response to the “rise of China,” proof that the U.S. state has rediscovered its industrial muscles after decades of neoliberal neglect.

But federal legislation is only the preface. The CHIPS Act does not build a single access road, wastewater plant, or cooling tower. Those are the purview of state agencies, municipal planners, water utilities, and development boards who have to make the basic arithmetic of high-tech production work in specific places. In the U.S., that means working through a state apparatus that is fragmented by design. Authority over land use, utilities, permitting, and taxation is dispersed across levels of government and specialist agencies. Industrial strategy, such as it is, becomes a patchwork of experiments and improvisations rather than a single coherent program.

Arizona has been unusually aggressive in turning that patchwork into an advantage. Since the mid-2010s, institutions like the Arizona Commerce Authority (ACA), the Greater Phoenix Economic Council (GPEC), and Arizona State University have converged around a shared anticipatory posture. They have streamlined permitting, prepared industrial parks in advance of firm commitments, and aligned workforce programs with projected labor needs. They have also learned to perform for federal and corporate audiences, marketing Arizona as indispensable to national security and technological sovereignty.

This is what I call techno-statecraft: the work of assembling state power through infrastructural provisioning, institutional adaptation, and coalition politics in order to produce “investable” territory. Readers of this newsletter will no doubt be familiar with all of its implications. Rather than a single developmental blueprint, techno-statecraft is a conjunctural formation—a way of aligning public capacities and private imperatives in the name of resilience, innovation, or security. In Arizona, it has coalesced around semiconductors.

To see how, we need to rewind.

A long history in speculative growth

A nation which does not expand is marked for decay… When opportunities for expansion present themselves they must be taken advantage of at once or the opportunities may not come again.1

Arizona did not wake up one morning and discover industrial strategy. Its semiconductor moment sits on top of a century of experimental development models, speculative booms, and institutional inventions that trained the state to treat land, infrastructure, and external capital as raw materials for growth.

The pattern was visible as early as the 1910s, when reports of oil seeps triggered a flurry of petroleum speculation. Promoters sold stock by promising that Arizona—wedged between Texas and California—would share in their hydrocarbon wealth. The oil never came; the wells were largely dry by 1918. What remained, however, was a political and business class accustomed to thinking of territory as an object of promotion and financial leverage.

That basic logic resurfaced in the Cold War. From the 1950s onward, Phoenix was transformed from a peripheral desert city into a node in a dispersed defense-industrial geography. Federal housing policies swelled the metropolitan population, while Pentagon contracts and presidential directives encouraging industrial dispersal drew electronics and aerospace firms into the region. Motorola opened a federally backed semiconductor lab in 1949. By the early 1960s, manufacturing output had increased nearly tenfold, and firms like Goodyear Aerospace, General Electric, and later Intel and IBM, embedded Phoenix in national electronics supply chains.

This new growth was not spread evenly. Many of these plants operated as branch facilities with limited local supply chains and externalized decision-making. Jobs and fixed capital arrived, but procurement and higher-end activities remained elsewhere. By the 1980s, local elites found themselves displaced by multinational executives whose allegiances were global rather than regional. Inter-municipal competition over water and tax base intensified.2 The same period saw the rise of speculative real estate as Phoenix’s dominant economic engine: deregulated savings and loans funnelled billions into risky land deals, culminating in catastrophic collapses and taxpayer-backed bailouts.

The response was not to abandon speculative development but to retool it. Business leaders and politicians turned to high-tech manufacturing as a more respectable face of the same growth model. Organizations like the Greater Phoenix Economic Council were created to coordinate recruitment of tech firms and polish the region’s image as a “business-friendly” innovation hub. After the 2008 housing crash wiped out hundreds of thousands of jobs, this strategy took on new urgency. The Arizona Commerce Authority was established in 2011 as a public-private agency charged with centralizing economic development, deploying incentives, and courting globally competitive industries.

By the time CHIPS arrived, then, Arizona had decades of experience in mobilizing land, infrastructure, and political access to attract mobile capital. What changed in the late 2010s was the scale and geopolitical framing of the opportunity. Semiconductors promised not just jobs or tax base, but a role in the national drama of technological rivalry with China. That promise gave state and regional actors a powerful narrative to attach to their longstanding growth machinery.

How to make a territory investable

The work of techno-statecraft is rarely spectacular. It looks less like a dramatic policy announcement and more like a series of negotiated decisions about pipes, parcels, and bond issuances. Intel’s long-standing presence in Chandler and TSMC’s arrival in North Phoenix make this process a bit more concrete.

Chandler was an early laboratory. leveraging the ecosystem built around Motorola, Intel began operations there in the 1980s and has expanded its Ocotillo campus through multiple generations of fabs. Over time, the city’s planning apparatus was effectively reshaped around the firm’s needs. Chandler pursued free-trade zone status, extended water and wastewater networks, and built subsidized utility corridors to serve the campus. As Intel prepared for new production lines, it secured up to $7.9 billion in CHIPS funding—nearly $4 billion of that for its Arizona operations. The city, in turn, embarked on major capital outlays for water and wastewater systems, road upgrades, and energy infrastructure aligned with Intel’s growth trajectory.

By 2024, Intel’s facilities drew roughly 15 percent of Chandler’s water supply, even as the city’s overall capital program for water infrastructure more than tripled compared to 2019.3 Planners responded by passing ordinances that require large industrial users to self-fund water access beyond a certain threshold—an attempt to contain the fiscal exposure of building bespoke infrastructure for a single mega-customer. But the fundamental asymmetry remains as Chandler is deeply invested in Intel’s presence, while Intel retains the ability to reallocate production across its global footprint.

North Phoenix illustrates a newer, more expansive variant of the same logic. In 2020, TSMC announced that it would build a fabrication facility in Phoenix. That initial $12 billion commitment has since ballooned into more than $165 billion in planned investment, making it the largest foreign direct investment package in U.S. history. Federal support has been substantial—$6.6 billion in CHIPS subsidies, plus tax credits—but the deal rests just as heavily on state and municipal undertakings.

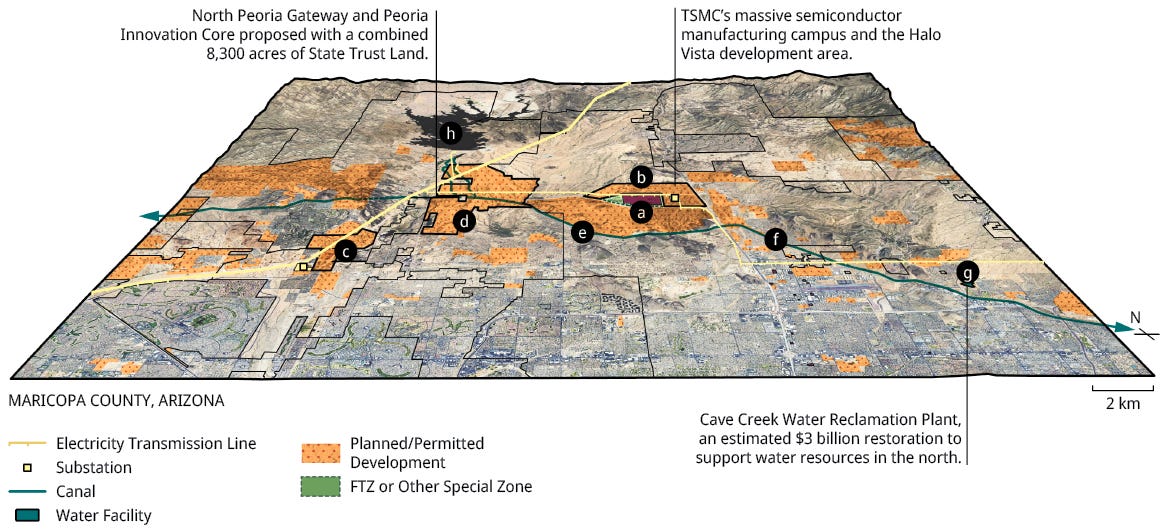

From the outset, Phoenix, ACA, and GPEC moved to prepare what would become a sprawling science and technology park in the city’s far north. The city pledged over $200 million for roads, sewers, and water systems; expedited land-use approvals; and pursued a Free Trade Zone designation to secure customs and tax advantages for TSMC and its suppliers. In 2023, Phoenix committed an additional $300 million to reviving the long-dormant Cave Creek water treatment plant, boosting capacity by 6.7 million gallons per day—theoretically enough to serve 25,000 households—in order to free up potable supplies for industrial use and enable large-scale real estate development around the fabs.

The Arizona State Land Department, closely linked to ACA, has complemented these moves by auctioning and leasing state trust lands surrounding the TSMC campus. Proceeds are channelled into infrastructure and workforce training directly tied to semiconductor expansion. University research parks have launched chip-focused training programs while suppliers like Applied Materials, ASM, and LCY Chemical have been courted to build adjacent facilities, knitting the area into a vertically integrated ecosystem.

Territoriality of North Phoenix Technology and Real Estate Expansion Complex

Combined, these interventions look less like isolated “incentives” and more like an infrastructural choreography. Water plants, roads, zoning overlays, university curricula, and land auctions are aligned to pre-empt bottlenecks and reassure firms that Arizona can shoulder the physical and institutional risks of expansion. This is techno-statecraft in practice—not a single plan, but a series of coordinated moves that transform a patch of desert into a landscape formatted for high-tech production.

The question is not whether this is skillful. It is. The question that matters for most people is…

Who carries the risk?

The conventional way of celebrating Arizona’s semiconductor boom is to tally jobs, GDP contributions, and headline investment figures. That accounting rarely asks how risks are distributed across firms, governments, communities, and ecologies.

At the most basic level, cities like Chandler and Phoenix are taking on long-term liabilities to support fabs whose productive lifespans and future profitability are uncertain. They issue bonds for water and wastewater plants, expand road networks, and reconfigure zoning to accommodate industrial campuses and their real estate halos. These decisions lock in infrastructures that will require maintenance and upgrading long after initial subsidies expire. All of this is not to mention the long-term impacts and speculative overbuilding of suburban sprawl that has long characterized Phoenix’s growth.

Resource risk is layered on top. In a semi-arid region already grappling with over-allocated rivers and intensifying drought, dedicating large and growing volumes of water to fabs is a political choice. Intel’s 15 percent share of Chandler’s water portfolio, and Phoenix’s commitment to repurpose the Cave Creek plant for industrial demand and associated growth, effectively shift hydrological risk away from firms and onto public systems and, ultimately, residents. The technical language of “reclaimed water” and “efficiency” often obscures the blunt fact that some uses are being prioritized over others, now and in the future.

Fiscally, the model builds in asymmetry. Corporations negotiate site-specific deals, secure federal subsidies, and benefit from state-built infrastructure. If market conditions or corporate strategies change, they can scale back investment or shift production elsewhere, as Arizona learned when Motorola gradually disassembled its Phoenix operations in the 1990s and 2000s. Municipal governments, by contrast, are left with sunk costs and debt obligations denominated in concrete and pipe.

There is also a democratic dimension. Many of the key decisions that shape Arizona’s semiconductor landscape are made through quasi-public or public-private bodies—the ACA, GPEC, technology councils—whose accountability is far thinner than that of elected councils. State audits have already raised concerns about opaque spending and elite courting, even as these organizations position themselves as stewards of a new “strategic” economy. Infrastructure-led growth advances through extra-democratic channels precisely because speed and certainty are central selling points to mobile capital. That is not a side effect—it is part of the pitch.

To be clear, the point is not that industrial strategy is inherently undesirable, nor that semiconductor manufacturing should somehow revert to the pre-CHIPS status quo. The point is that the current model of techno-statecraft—coalition-driven, infrastructure-intensive, framed by geopolitical urgency—is being built with remarkably little public debate about its long-term implications. Industrial strategy is being treated as a technical problem of capacity and competitiveness, when it is also a political problem of territorial reorganization and risk distribution.

A brief contrast helps clarify this. The very firm now reshaping North Phoenix, TSMC, emerged from a different trajectory in Taiwan. There, semiconductor development was anchored in a state-led strategy centered on national science parks, with utilities and land-use policies organized to secure firms’ growth as a matter of national priority. That model had its own profound social and ecological costs—from farmland conversion to water conflicts—but it rested on a more centralized institutional architecture. Arizona’s model, by contrast, is fragmented and coalition-driven, relying more on a web of agencies, utilities, and developers to do the work of translation between federal ambition and local landscapes.

It’s not that one model is better than the other in the abstract. It is that techno-statecraft is not a neutral or inevitable response to technological change. It is a political choice about how to organize state power, infrastructure, and territory around certain industries and narratives. Those choices can, in principle, be made differently.

For now, Arizona’s leaders are doubling down for what is surely a massive boon to state economic growth. They have opened a trade office in Taipei, signed supply-chain agreements with Taiwan’s Bureau of Foreign Trade, and secured a CHIPS R&D Flagship designation for Arizona State University. The state’s development boards convene industry executives and diplomats as matter-of-factly as earlier generations hosted land promoters and oil men.

Nevertheless, the fabs rising over the desert are real. So are the jobs they bring. But so, too, are the pipelines, bonds, and political arrangements that make them possible. High-tech industrial strategy has become the latest chapter in a much longer story of speculative growth that continues to this day. The massive growth in suburban sprawl is a testament to the continuation of this model, but also its fragility.

References

Phoenix Gazette, circa 1900. Quoted in Luckingham, Bradford. 1989. Phoenix: The History of a Southwestern Metropolis. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press: 48.

Shermer, Elizabeth Tandy. 2013. Sunbelt Capitalism: Phoenix and the Transformation of American Politics. Politics and Culture in Modern America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press: 306–307.

Intel. 2024. “2023-24 Corporate Social Responsibility Report.” https://csrreportbuilder.intel.com/pdfbuilder/pdfs/CSR-2023-24-Full-Report.pdf; Also see: City of Chandler. 2020. “2020-21 Annual Budget: ‘The Future’s in Sight’”; City of Chandler. 2023. “2023-24 Annual Budget: ‘Innovation at Work.’”