The Compute-Industrial Complex

Inside some of the coalitions turning America’s AI boom into a new model of infrastructural enclosure, deregulation, and state-capital coordination

Industrial policy is not decreed by a central committee or a cadre of autonomous bureaucrats. In the U.S., it is crafted through sprawling coalitions linking firms and financiers to “experts,” policy advocates, staffers, and even self-proclaimed “activists” who translate corporate needs into public policy. What we rarely see—and what this article only begins to map—is who these actors are and how their coordinated efforts shape policy across municipal, state, and federal scales.

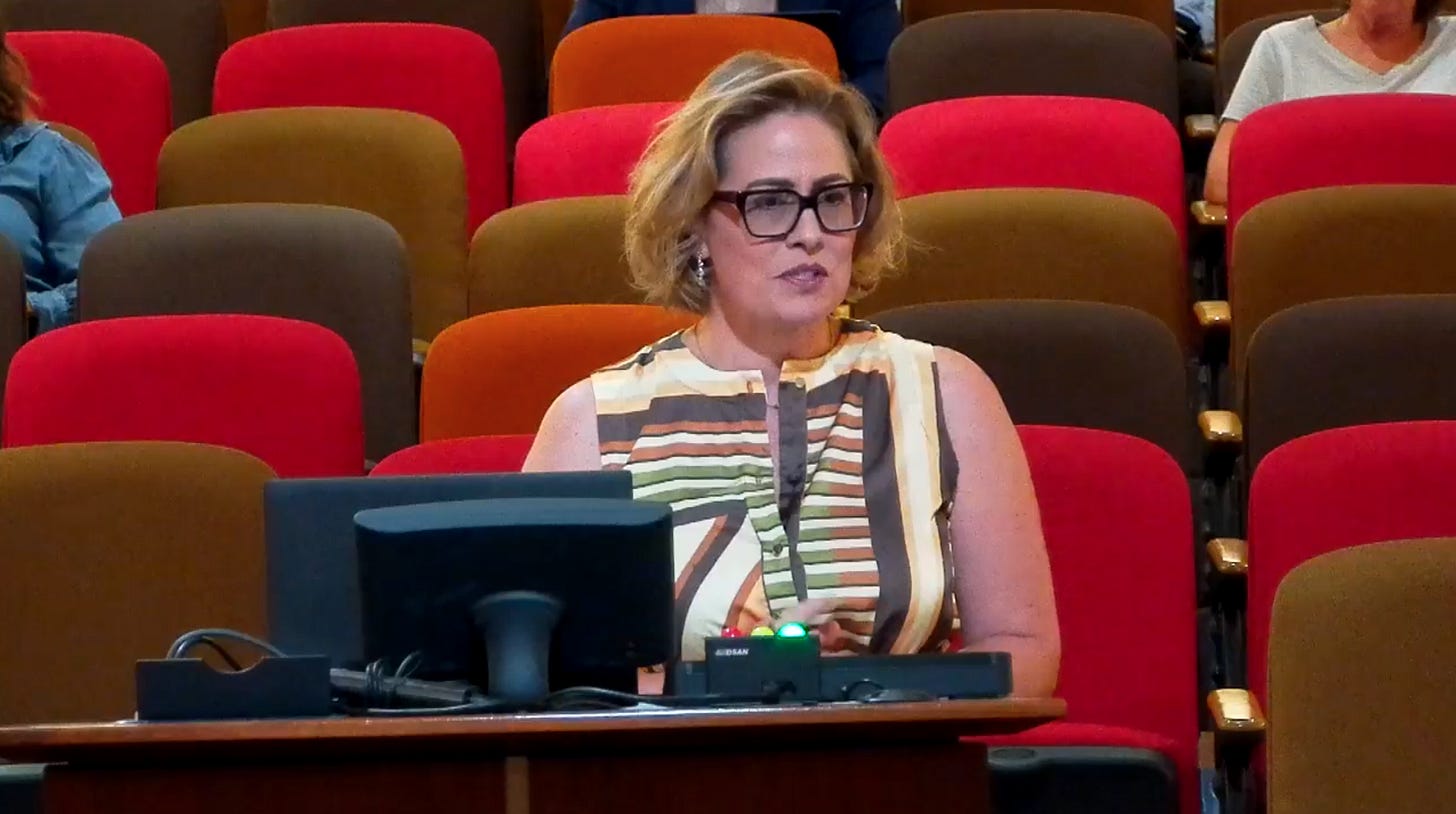

An unscheduled visit by Kirsten Sinema…

Chandler’s Price Corridor was not supposed to host a new data-center campus. City staff and segments of the public had pressed for uses that fit the district’s established “high-wage, knowledge-industry” vision, and skeptics argued that a data center—low headcount, heavy utility footprint—would undercut that model. In my own research, Chandler’s planners told me they had a system in place to reserve the city’s water for higher-value uses which, at the time, included Intel’s CHIPS-era expansion (what they called “quality of life” water). Given data centers’ low headcounts and heavy utility demand, many proposals have been rejected. These proposals shifted to Mesa and west Phoenix, yet Chandler’s Intel-driven water-system upgrades remain a coveted draw for data-center developers. Into this fraught, locally bounded land-use debate stepped Kyrsten Sinema on October 16, 2025, appearing during the council’s unscheduled public comment period to advocate for what she called an “AI data hub.” No longer a senator, she came, rather, as the founder and co-chair of the AI Infrastructure Coalition which she says was working with the Trump administration.

No longer a senator, Sinema led with her new credentials, the “founder and chair of the AI Infrastructure Coalition,” describing AI as a “national security imperative” and positioning Arizona as one of five states “best poised to lead.” The city’s 2016 Price Corridor plan, she argued, pre-dated today’s technology stack and therefore the corridor needed to adapt: “Back nine years ago, the general plan didn’t even mention AI or AI data centers or AI hubs.” What looked like a conventional “data center” to local planners—“a regular data center that holds cat memes and your 7-year-old bank accounts”—was, in her framing, categorically different from AI-class compute: “AI data centers are the Lamborghini when compared to the old data centers’ Pintos.”

She tethered this reframing to labor and competitiveness. The corridor’s existing employers, including several financial-services call centers, would see rapid automation: “In less than five years, those will be obsolete, completely replaced by AI and AI companies.” The proposed hub, by contrast, would anchor the infrastructure that future firms require: “They create a massive amount of compute power—the very power that AI companies of tomorrow need in order to relocate here in Arizona.”

The rhetorical pivot came in her close, where local zoning gave way to federal authority. Citing a prior Planning Commission vote to advance the project, Sinema warned that rejecting the plan would only delay the inevitable:

“That site will remain empty if not developed under this plan—until federal preemption comes, which is coming, and it is coming soon.”

What does a suburban growth-district fight over use mix and job quality have to do with national AI industrial policy? Sinema’s remarks convert a municipal siting dispute into a question of preemption, grid capacity, and ‘AI-ready’ infrastructure—the preferred language of a new coalition politics in the Trump era.

What is the AI Infrastructure Coalition?

A search for the AI Infrastructure Coalition (AIC) yields almost nothing. Digitally, it’s a ghost. Though, what little appears on these sorts of organizations’ websites that do exist hardly conveys the extent of what they actually do.

The AI Infrastructure Coalition (AIC) first surfaced publicly through a formal response to the federal AI Action Plan request for information, submitted in March 2025. The twelve-page memo—filed “on behalf of the AI Infrastructure Coalition” by the policy consultancy CO2EFFICIENT—lays out an agenda to retool U.S. infrastructure policy around AI-driven energy and compute demand. Its language reads like an industrial blueprint put forward by many others in the same RFI: whole-of-government coordination, new “AI Development Zones,” interagency reforms to accelerate power, water, and cooling infrastructure for advanced data centers, etc. Beneath the rhetoric of innovation and national security, the filing sketches a new regulatory perimeter that treats compute as the organizing logic of territorial development.

The AIC describes itself as “a national coalition of companies and experts representing the digital infrastructure ecosystem,” with a deliberately expansive remit spanning “AI platform providers, microchips, server hardware, data-center equipment, software developers, data-center operators, and power-management services.” Yet it names no members, only sectors. The coalition’s public face, Kyrsten Sinema, apparently chairs and speaks for it at municipal hearings and recent industry conferences. Her own framing tracks the AIC memo: AI is a “national security imperative” requiring “a whole-of-government approach,” led by a handful of “strategic states.” Arizona, she argues, is one of them. This logic reframes local siting disputes as pieces of a geopolitical campaign to preserve U.S. technological dominance.

The coalition’s memo centers on infrastructure bottlenecks—grid congestion, permitting delays, and inadequate cooling—and prescribes policy tools keyed to corporate investment timelines. It urges the federal government to extend FERC Order 2023’s interconnection reforms and implement Order 1920-A on long-term transmission planning—positions hyperscalers have endorsed (context I cover in a Trump 2.0 AI industrial strategy post). It calls for federally brokered “collaboration” between utilities and large-load customers to scale tariff structures that enable new business models, steer siting toward available capacity, harmonize data-center efficiency standards, and expand DOE-led R&D on cooling and heat-reuse. Most ambitiously, it proposes a dedicated executive-branch “policy home” for data-center policy, consolidating oversight now dispersed across local utilities, environmental agencies, and planning departments.

Based on the available evidence, this agenda functions as preemption-by-policy already taking hold in multiple states (I’ll cover this in a forthcoming post). It advances a framework that narrows municipal authority—limiting cities like Chandler from setting land use or fully accounting for water and energy costs. The “AI Development Zone” language (akin to proposals from the Institute for Progress) reprises familiar instruments—enterprise zones, opportunity zones, and other deregulatory regimes that fast-track private capital under the banner of national competitiveness. By grafting compute infrastructure to national-security rhetoric, the AIC recasts industrial lobbying as patriotic duty. In Sinema’s framing, resisting a local data-center project becomes tantamount to opposing America’s bid for AI “global dominance.”

AIC’s affiliates tell us more about how industrial strategy is being crafted today.

Behind the AIC is a constellation of expert networks and trade groups organized by CO2EFFICIENT, each aimed at a specific bottleneck in the AI buildout. CO2EFFICIENT’s team includes ex-BP legal/public-affairs leadership, a House Energy and Commerce deputy counsel, FERC and congressional energy staff veterans, a leading advocate for large electricity buyers, and AWS’s former senior corporate counsel on AI/data-center regulation, among others. In short, these are specialists in utilities, pipelines, gas, transmission, and hyperscale data-center policy.

The AI Supply Chain Alliance (AI-SCA) frames itself as an effort to secure the “resilience and competitiveness” of the AI manufacturing base. Its membership reads like a supply-chain schematic—Dell Technologies, NVIDIA, Supermicro, Schneider Electric, Shell, Trane Technologies, Flex, ENEOS, Prometheus Hyperscale, and others—spanning chip design, server hardware, energy systems, and industrial cooling that directly support hyperscale AI facilities. The alliance’s own RFI response to the AI Action Plan describes AI as critical national infrastructure and warns of permitting and power barriers that are “stymying the digital infrastructure ecosystem.” The argument mirrors AIC’s—AI capacity should be treated as strategic infrastructure deserving of streamlined approvals and targeted incentives.

The Electricity Customer Alliance (ECA) operates as the energy-facing branch of this ecosystem. It represents “large electricity customers” and counts Google, General Motors, Freeport-McMoRan, RWE, and Steelcase among its members (ECA Members). Its senior advisor Tom Hassenboehler—a partner at CO2EFFICIENT—has testified before Congress on “Powering AI: Examining America’s Energy and Technology Future.” ECA advocates for “customer-centric” grid modernization, a euphemism for ensuring hyperscale data centers can secure dedicated transmission capacity, flexible tariffs, and interconnection priority. In practice, the group functions as a policy arm for power-hungry AI clients, embedding their load demands within ongoing federal grid reforms under FERC Order 1920.

If ECA covers electricity, the Liquid Cooling Coalition (LCC) handles heat. Founded by Intel, Shell, ENEOS, Supermicro, Vertiv, Submer, and Ada Infrastructure, the LCC promotes liquid-cooling standards and R&D programs for high-density AI servers. Its filings for the AI Action Plan argue that advanced cooling is essential to meet the thermal demands of AI systems. The group pushes for DOE and national-lab partnerships to expand cooling technology deployment, reinforcing the notion that AI’s physical intensity is an engineering inevitability rather than a policy choice.

Finally, the Natural Gas Innovation Network (NGIN) links the digital buildout to the fossil fuel sector, building on the Differentiated Gas Coordinating Council (DGCC). Public member listings include Sempra, Southern Company, Williams, BKV Corp., Kuva Systems, and Project Canary. The network is “dedicated to enhancing the transparency of the natural gas value chain, fostering technological innovation, and reducing emissions,” positioning gas as a cleaner, more traceable firm-power option for new AI loads. Remarks by Brad Crabtree—then at DOE, now an ExxonMobil executive—at a DGCC workshop hosted by Tom Hassenboehler and CO2EFFICIENT and posted on DOE’s website promote a U.S. energy policy tailored to AI demand, legitimizing a subsidized public–private alliance—“differentiated” gas, carbon capture, and hyperscalers—to secure gas-fired power for data centers under a decarbonization veneer.

These coalitions form an integrated policy stack: AI-SCA builds, ECA powers, LCC cools, and NGIN fuels. Each advances a partial solution to the same problem—how to guarantee uninterrupted compute growth under the auspices ‘innovation’ and ‘security.’ Collectively, they constitute a deliberate architecture of techno-industrial power—a compute-industrial complex that rewrites energy and environmental governance around AI’s physical demands.

These coalitions are just a small part of a much larger organizational apparatus.

At the macro level, this coalitional architecture signals a new phase of state-capital entanglement—what I’ve been referring to as techno-statecraft. Unlike earlier state-led industrial planning that at least nominally weighed public benefit against private interest, today’s model is driven by “policy entrepreneurs” like CO2EFFICIENT, which broker coordination across corporate and financial actors. By managing multiple coalitions—AIC, ECA, LCC, AI-SCA, and NGIN—the firm operates as a clearinghouse for capital, translating corporate requirements into national policy language. In practice, this privatizes the infrastructure agenda—drafting rules, shaping regulatory frameworks, and embedding proposals through public comments, legislative briefings, and closed-door negotiations.

These organizations function less as trade groups than as brokers—intermediaries between corporate interests and the state. They translate technical requirements—megawatts, megabytes, and water gallons—into the language of national policy. Their shared grammar of inevitability casts AI expansion as both unstoppable and essential to security, warranting an “all-of-government” mobilization. The result is a quiet but far-reaching restructuring of public authority on the back end of AI growth, where decisions over land, energy, and environmental limits are reframed as throughput problems for industry to solve.

The Chandler case shows that this infrastructure politics is already territorial. When Sinema told city officials that “federal preemption is coming,” she was not making an idle threat. She was articulating a governing logic that treats local planning as an obstacle to be bypassed in the name of so-called “national competitiveness”—now synonymous with corporate profit. The emerging AI industrial regime combines technological determinism with state facilitation. It represents a form of infrastructural empire building in which the state guarantees the conditions for capital accumulation through land, energy, and law, so long as it can be justified as powering AI.