Behind the Federal Power Grab to Fast-Track AI

Inside FERC’s queue reforms, co-location fights, and a new national interconnection push as data centers transform grid governance

H.R. 4776, the “SPEED Act,” just passed the house yesterday, December 18, 2025. It’s basically a major overhaul bill that would speed up and lock in federal approvals for big energy and infrastructure projects (most likely for data centers) by shrinking environmental review and making it much harder for communities or courts to slow or stop projects once they’re approved. If this passes the Senate, I will do a deeper dive into its implications. Yet, permitting overhaul has been a years-long project to fast-track data centers. In this article, I look at the role of FERC and corporate influence in its governance of the grid as it also explores a nationalized framework that could diminish local and state authority over energy permitting.

AI data centers are making the electric grid the new choke point for growth, and inside FERC’s rulemaking and leadership politics, the biggest companies are increasingly able to turn “grid access” into guaranteed, preferential power.

Many parts of the U.S. power grid are already under stress. Old power plants are retiring, key transmission corridors are crowded, and it can take years for new projects to get approval to connect. Into that system come AI data centers and other hyperscale facilities that need enormous amounts of electricity, sometimes as much as a small city. Their developers want firm dates for when power will be available, and they often want to match their use to particular power sources. That scale creates hard choices with real consequences for everyone else. If the grid has limited capacity, regulators have to decide who connects first, what upgrades must be built, and who pays when new demand raises costs or increases the risk of outages. Those decisions shape household bills, local reliability, and whether communities end up subsidizing private growth.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, is the federal agency that sets many of the rules that make these outcomes possible. It oversees the technical and legal terms for connecting to the grid, using the transmission system, and paying for upgrades. Most of this happens through formal filings and written comments, not public meetings. For companies racing to build AI capacity, these behind-the-scenes processes can determine whether a project moves forward on schedule or gets stuck for years. Large tech firms increasingly show up in these proceedings, pushing for faster connections and clearer pathways to secure power. Google and Amazon, for example, have submitted comments and participated through energy affiliates. Some grid operators (like PJM) also partner with tech firms (like Google) on AI-driven interconnection planning tools which further ties corporate interests to the administrative machinery of grid expansion.

This is why personnel and priorities inside FERC matter. It is not a detached tribunal or impartial experts. It is a politically appointed institution whose judgments about urgency and fairness shape which reforms happen, and whose interests are protected. In that sense, the fine print of grid governance becomes a major lever for AI expansion, and a quiet site where public costs, private timelines, and system risk are negotiated.

This article is part of ongoing commentary related to AI industrial policy (parts I, II, and III) and the rise of Fossil AI. Please check out these articles for further background.

FERC’s rulemaking ecosystem

Several recent FERC actions show how the push to power AI and data centers turns into binding rules that shape who gets electricity, how fast, and on what terms.

Let’s begin with the interconnection queue—the long line of power plants and grid-scale projects waiting for permission to connect to the grid. In Order 2023, FERC overhauled the generator interconnection process. Instead of studying new generation requests one by one in a “first-come, first-served” line, transmission providers must study them in clusters under a first-ready, first-served approach. FERC also tightened “commercial readiness” rules to reduce speculative requests—requiring stronger site control and larger readiness deposits to enter and remain in the queue. The aim was to fix an interconnection system that had become slow, backlogged, and difficult to manage. But this also means that projects with more money, land secured, and staff capacity can move forward more easily than smaller or less prepared developers. The Clean Energy Buyers Association, which represents large corporate buyers such as Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta, argued that faster interconnection was essential to meeting clean energy goals. The final rule adopted many of the changes it supported, including grouped studies, stricter screens, and tighter timelines.

Transmission planning moved at the same time. Order 1920, issued in 2024 after a proceeding that began in 2022, requires 20-year regional transmission planning using multiple scenarios and directs regions to establish clearer up-front methods for allocating the costs of major new regional lines. For many customers, this matters because transmission is expensive and hard to build. Decisions about planning horizons and cost allocation can shift costs across states, utilities, and ratepayers for decades. Investor-backed developers and industry groups such as WIRES supported clearer rules because they reduce uncertainty for investment. Private equity has also adjusted its strategy around these constraints as it buys up energy and data center assets. Blackstone’s purchase of the 620 MW Hill Top gas plant in Pennsylvania has been described as a way to pair a power source with data center demand, reduce exposure to long queue delays, and deliver power fast enough for AI buildouts.

Relatedly, the most contested issue has been “co-location,” which is when a large data center sits next to a power plant and tries to take power directly, with less reliance on the wider grid. In 2024, FERC rejected amendments tied to a Talen and Amazon arrangement at the Susquehanna nuclear site, and the dispute moved into appellate review. The case became a test of where to draw the line between private arrangements and shared public systems. For developers, co-location can look like a shortcut around delays and network upgrade charges. For the grid, it raises a basic fairness problem. If a large private load uses the plant as an anchor but still depends on the broader system for backup, balancing, and contingencies, who is responsible for the resulting costs and risks?

That question sharpened in 2025. On February 20, 2025, FERC opened a show-cause proceeding involving PJM Interconnection and PJM transmission owners, drawing on a November 2024 technical conference and a complaint by Constellation against PJM. FERC asked whether PJM’s tariff, which is the rulebook that governs rates and service terms, clearly covers co-located load. Beneath that procedural issue was a practical one. Can a power plant effectively serve as a private power source for adjacent computing facilities while the regional grid still absorbs volatility, reliability obligations, and the financial consequences of system stress.

Two additional pressures pushed the issue toward a decision. PJM’s independent market monitor warned that approving large new data center loads without enforceable service conditions could lead to curtailments when the system tightens. Curtailments could fall on data centers, existing customers, or both. At the same time, federal officials pushed for speed. On October 23, 2025, the Department of Energy sent a Section 403 “Large Loads” letter directing FERC to start a rulemaking to accelerate the interconnection of large loads, explicitly including AI data centers. In that framing, delay is no longer just a technical inconvenience. It becomes a national constraint, and interconnection becomes a tool of industrial policy.

On December 18, 2025, FERC acted by ordering PJM to establish clear rules for co-located AI data centers and other large loads—one day after PJM reported record-high capacity auction prices linked to rising data center demand. It found PJM’s tariff unjust and unreasonable because it did not provide clear, consistent terms for customers serving co-located load and for customers taking transmission service on their behalf. In practical terms, FERC pushed PJM to adopt enforceable requirements, tighten accounting practices that can make loads look smaller on paper, and create faster pathways for new generation to interconnect. The aim is to move the buildout forward, but also to make the costs and reliability duties harder to shift onto everyone else.

Personnel is policy

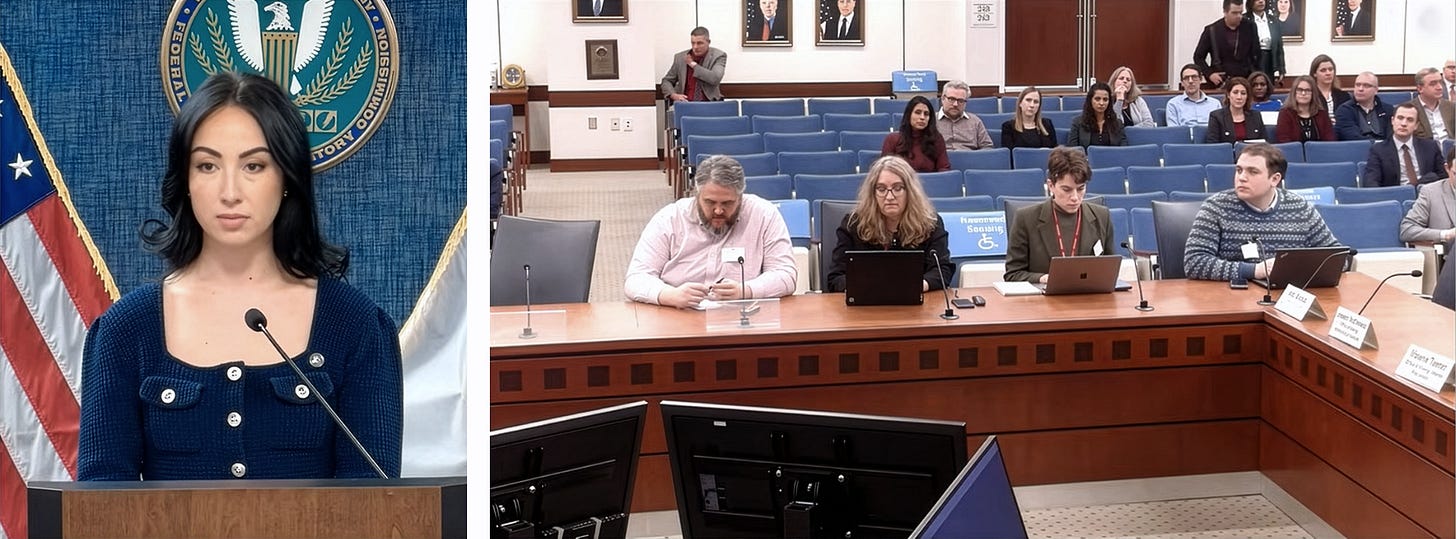

The December order matters on its own terms, yet its technical language can obscure how nominally “independent” commissions like FERC may work in practice. Recent public arguments by the chair of the FCC have also underscored how contested that independence is, especially when executive priorities of the Trump administration pressure regulatory agendas. What happens next will depend on how FERC, through its five commissioners, continues to define the problem, set priorities, and balance speed for new large loads against reliability, cost shifting, and the obligations of the shared grid.

FERC is run by five commissioners who vote on major orders and rulemakings. Their professional backgrounds influence what they see as the core problem, which risks they prioritize, and what solutions they consider practical. The chair also matters because the chair sets internal management priorities and helps decide what comes onto the agenda.

In November 2024, then-Chair Willie Phillips dissented when FERC rejected PJM’s proposed approach to the Susquehanna co-location arrangement. He warned that the decision could threaten reliability and raised national security concerns in the context of growing data center demand. In February 2025, he issued a concurrence that placed that dissent within a growing Commission record on co-location. Soon after, Chair Mark Christie led a unanimous vote to open a formal review of co-located large loads in PJM, framing the issue as the need for clearer tariff terms, reliable operations, and fair cost allocation. From the outside, it is hard to see exactly what internal judgments shifted at each step, but the larger point is clear: leadership turnover can change the Commission’s priorities and pace, and therefore who has influence over what comes next.

Phillips resigned in April 2025 after the White House asked him to step down, and Trump later nominated David A. LaCerte to fill the seat, placing a new commissioner directly into FERC’s intensifying fights over data centers. Christie’s term expired June 30, 2025; the administration chose not to renominate him and moved to replace him with Laura Swett, amid reported White House pressure on FERC to move faster on “baseload” and fossil fuel infrastructure to meet rising demand. These moves preserved a 3–2 Republican-Democratic split, but they also shifted the Commission’s internal balance and direction, especially as Christie publicly criticized DOE’s large-load interconnection push as an overreach into state authority.

LaCerte’s profile is not the standard power market resume. FERC’s biography describes him as having two decades across public service, law, and regulatory policy, including senior roles at the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, and in a Louisiana cabinet position. He was confirmed on October 7, 2025, for a term expiring June 30, 2026. Reporting also highlighted links to Project 2025 and treated the nomination as part of a broader push to reshape regulatory governance. For lay readers, the takeaway is practical. FERC is now dealing with problems that look less like routine market tuning and more like physical bottlenecks. Interconnection delays, siting conflict, and tight reliability margins have become constraints on rapid AI expansion. A commissioner with a strong executive-branch management background may approach those constraints with a different style and different priorities.

Swett’s rise to chair soon after LaCerte’s confirmation may also point toward a wider energy buildout approach that includes natural gas infrastructure (see my article on Fossil AI). FERC’s biography describes her as having spent fifteen years litigating FERC matters for generating utilities, transmission owners, and pipelines, most recently at Vinson & Elkins. She decided not to recuse from certain data center-related matters involving a former-firm client and appointed a former Vinson & Elkins colleague to general counsel. These details matter because they connect FERC’s leadership to a professional world built around tariff design, regulatory litigation, and the legal work that makes large infrastructure projects possible—particularly for fossil fuel interests.

Vinson & Elkins’ was founded in Houston in 1917 during a Texas oil boom and has long specialized in the legal architecture of energy development. As is (I hope) evident at this point, energy systems require more than physical construction—they require legal machinery that secures access to land and capital, obtains permits, and stabilizes price formation through enforceable rules. The firm describes representing clients before FERC, regional grid operators, and state commissions in multi-billion-dollar proceedings, with clients across utilities, pipelines, producers, generators, and power marketers. It also emphasizes its long involvement in U.S. LNG export and import projects and its experience across the federal agencies that oversee LNG among other fossil fuel industries.

As the grid becomes the main permitting bottleneck for AI, energy regulatory law firms are becoming key intermediaries between infrastructure and capital. They help turn network capacity into a contractual right and an investable asset—credible to investors and regulators alike. Their influence becomes most visible when new loads arrive at scale and FERC has to decide what kind of certainty it will recognize for those loads, and what costs and risks it will allow to fall on everyone else.In PJM, those decisions are unfolding alongside a push to meet data center demand with new natural gas production, new power generation, and related infrastructure. This puts FERC’s December order directing PJM to clarify tariff terms into a broader perspective as these leadership changes may shape how FERC balances rapid AI load growth against the terms of a gas buildout that increasingly underwrites it.

The art of techno-statecraft

Across these dockets, it’s not just that AI uses a lot of electricity; it’s that a small group of powerful companies is learning how to turn that demand into enforceable advantages inside the grid’s rule system. Hyperscalers submit comments and push for faster ways to connect. Developers and transmission industry coalitions push planning changes that make new lines easier to approve and finance. Private equity looks for ways to secure power without waiting at the back of the line. The tactics differ, but the approach is the same. They do not merely build around regulation. They work through the rulebook so the rulebook works for them.

The “market” is not an external environment that law reacts to. Electricity is not as simple as supply and demand meeting on their own. This is what regulated infrastructure looks like in practice. The “market” is built through tariffs, cost-sharing rules, interconnection procedures, and the written records that justify them. These are not obscure technical details. They decide who gets priority, what counts as reliable service, who can rely on self-supply, and who stays exposed to congestion, price swings, and the costs of new upgrades.

Co-location makes the stakes easiest to see. FERC treated this as a tariff issue in its February 2025 show-cause proceeding, and that is a big deal because tariffs are where obligations become enforceable. In December 2025, FERC ordered PJM to write clearer terms for how co-located load is served and how transmission service works when someone takes service on the customer’s behalf. Whatever PJM writes now could become a model for other regions, shaping how future data centers get powered nationwide. This also matters because FERC (following the DOE directive) is also considering a national large-load interconnection framework (RM26-4-000) that could shift authority away from states. This follows suggestions by the Data Center Coalition (which includes the largest hyperscalers and others) in a Senate hearing back in February 2025 which advocated for the empowerment of FERC to override state authority on permitting projects deemed “in the national interest.”

Hyperscalers like Google have asked FERC for party status in RM26-4-000, arguing that its nationwide data centers give it a direct stake in the outcome (you can search theirs and other comments here). It also argued that in order to address the “foundational transmission issue” the U.S. should “adopt a holistic transmission planning process that optimizes grid development by accounting for both generators and the large loads planning to interconnect. … Absent a change of course, electric infrastructure appears to be the one pillar of our economy and our global competitiveness where we are increasingly falling behind, a result that would have devastating consequences for our economic growth and national security.” (Emphasis added, “Reply Comments of Google LLC” on Docket No. RM26-4-000: 3–4) Holistic planning may be sensible on its face, but it would also likely strengthen the position of the largest corporate buyers by making their load forecasts and timelines central to what gets built, while “competitiveness” and “national security” rhetoric serves to obscure this.

This is why FERC leadership and process matter. FERC does not govern through public speeches and open public hearings. It governs through what it puts on the agenda, how it runs formal proceedings, and how it writes orders that can survive rehearing and court review. That style of governing favors the parties that can hire specialist lawyers and experts, stay in long proceedings, and shape what counts as “reasonable” evidence and convincing argument—like the appeals to national security by Google quoted above. If you want to understand why outcomes tilt toward certain players, it helps to pay attention to who is in the room (literally and figuratively), who can afford to participate, and what professional networks and industry experience top officials come from. Not unrelated to its ongoing rulemaking efforts, FERC runs commissioner-led technical conferences on resource adequacy and reliability that have become tightly coupled to data center growth.

In sum, once new rules and pathways are created, speed and certainty become their own allocation mechanism. The parties who benefit most are those that can move immediately when a regulatory opening appears, locking in priority positions before competitors or publics can respond. Hyperscale operators can do this because they arrive with capital, repeatable site models, and a willingness to pay for accelerated outcomes, including bespoke infrastructure and contract structures that smaller customers cannot match. The long-run risk is a grid that increasingly serves large corporate customers as the default priority, while everyday customers and smaller businesses absorb more of the uncertainty, costs, and reliability risks that come with rapid buildout.