The United States in Venezuela I—How to Build an Oil Empire

How legal architecture, elite collaboration, and U.S. firms locked Venezuela into a century-long extractive order

Happy New Year…? Since December I’ve been working on a research piece on the U.S.-Venezuela conflict and recent events have compelled me to finish it. I will publish it in two parts, Part I (this) with Part II out in a few days.

The January 2026 kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and bombing of Venezuela marked the kinetic flashpoint of a Venezuela policy explicitly focused on oil “restitution.” In mid-December 2025, Trump ordered what he called a “total and complete blockade” of sanctioned oil tankers moving in and out of Venezuela—an interdiction campaign Caracas condemned as piracy—and, after the raid, the White House and allied commentators moved quickly to cast “rebuilding” Venezuela’s oil system as the central prize of the operation, with U.S. firms positioned as the primary beneficiaries.

Major outlets have read the escalation through a revived Monroe Doctrine frame, reinforced by the administration’s December 2025 National Security Strategy, which elevates the Western Hemisphere as a priority theater and explicitly links regional strategy to protecting and jointly developing “strategic resources” while denying rivals access. In some ways it may represent an acknowledgement of a multipolar world order with the U.S. empire on the back foot, retreating into domination of its own “back yard.” Taking perhaps a more systemic view, Grace Blakely argues that Trump’s Venezuela stance is a blunt oil-power strategy—use coercion and sanctions leverage to redirect Venezuelan crude away from China and toward U.S. firms. She frames this as a response to the shale contradiction—lower prices undermine U.S. frackers—so Venezuela becomes a geopolitical substitute for weakening U.S. energy independence. This is certainly plausible: see my article on Fossil AI on the rising involvement of natural gas for AI data centers. Yet it is probably more likely that the through-line is less a single coherent master plan than a convergence of aims—oil industry restoration, hemispheric primacy signaling, and China-denial—assembled opportunistically around a spectacle of force.

With all this in mind, let’s take a step back to see the broader arc of U.S. interest in Venezuela—to look past the chaos of the present and trace the invisible wires that have bound Venezuela to the north for over a century. As this two-part essay explores, U.S. influence in Venezuela was a slow and deliberate project achieved by rewriting laws, co-opting elites, and weaponizing the technology of extraction itself. Part I examines the historical foundations of this empire and the class divisions that set the stage for the Chávez-era conflicts. Part II will then analyze the sophisticated sabotage of the state-owned oil company by managers linked to U.S. firms and Venezuela’s subsequent struggle for technological sovereignty amidst relentless pressure by the U.S. security apparatus and global capital.

The Pacific System and the Architecture of Extraction

Long before the Monroe Doctrine hardened into a rigid policy of intervention, it existed as a sentiment known then as the “pacific system” of commerce (meaning rejecting the use of force as a policy instrument rather than the Pacific Ocean). While the contradictions of this system are evident in hindsight, it’s worth mentioning that many early U.S. statesmen were eager to compete with European imperial powers but remained too vulnerable to challenge them militarily. The idea was also not without diverging interpretations. Thomas Paine claimed that commerce was a pacific system where nations would be useful to one another through commercial interdependence rather than warring over claims.1 Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom, James Monroe, sought to place the pacific system on a secure basis through reciprocal respect from other powers (particularly Britain in this case). As president in 1823, Monroe shifted from a defensive posture to reveal a more assertive Doctrine that aimed to transform the Western Hemisphere into a closed sphere of influence.

The initial aspirations of the Bolivarian revolution initially mirrored the northern ambitions of the pacific system (at least as it existed in rhetoric). Simón Bolívar’s project of Gran Colombia—encompassing present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and Ecuador—was an attempt to create a sovereign counterweight to external European powers. Yet, Venezuela was birthed in the interstices of imperial conflict. The region was a theater for Spanish, French, British, and Dutch rivalries, its internal class struggles between elites and non-elites exacerbated by the shockwaves of the American, French, and Haitian revolutions. This fragility led to the faltering of the First Republic (1811–1812) in civil war, the collapse of the Second Republic (1813–1814) under Spanish reconquest, and the eventual dissolution of Gran Colombia (1819–1831) itself. The fragmentation of this project was not just a failure of governance but a geopolitical necessity for rising powers; the wedging away of Panama from Colombia in 1903 with U.S. support to facilitate plans for an isthmian canal remains the most blatant example of how U.S. empire-building relied on the atomization of Latin American sovereignty.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Venezuela had been integrated into the global capitalist system by competing imperialist powers, yet not as a sovereign partner. It was constructed as a specialized extractive enclave. While British and Dutch capital, represented by Royal Dutch Shell, had established the early footholds, the strategic imperatives of World War I fundamentally altered the landscape. The conflict laid bare the vulnerability of the West’s reliance on Middle Eastern or Asian oil. The United States, operating under an increasingly expansive interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, sought to secure a proximate, defensible reserve of hydrocarbons. British hegemony was displaced by a U.S. imperative to turn the Caribbean Basin into an energy security lake. By this time, communications technologies like the radio and telegraph had transformed the corporate world by allowing for communications to extend across oceans and continents and into areas with strategic resources much easier.

The key instruments were still institutional and legal, and a prime initiating factor was the dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez (1908–1935). Gómez provided the ruthless stability required for capital investment, trading national resource sovereignty for the political and financial backing of the United States. This was an active, strategic collaboration; by sedulously avoiding conflict with foreign powers and paying off Venezuela’s external debt, Gómez positioned his regime as a “reliable partner.” In exchange, Washington insulated his dictatorship from the democratic waves sweeping other parts of the world. However, the most profound act of colonization during the Gómez era was not the drilling of wells, but the writing of laws.

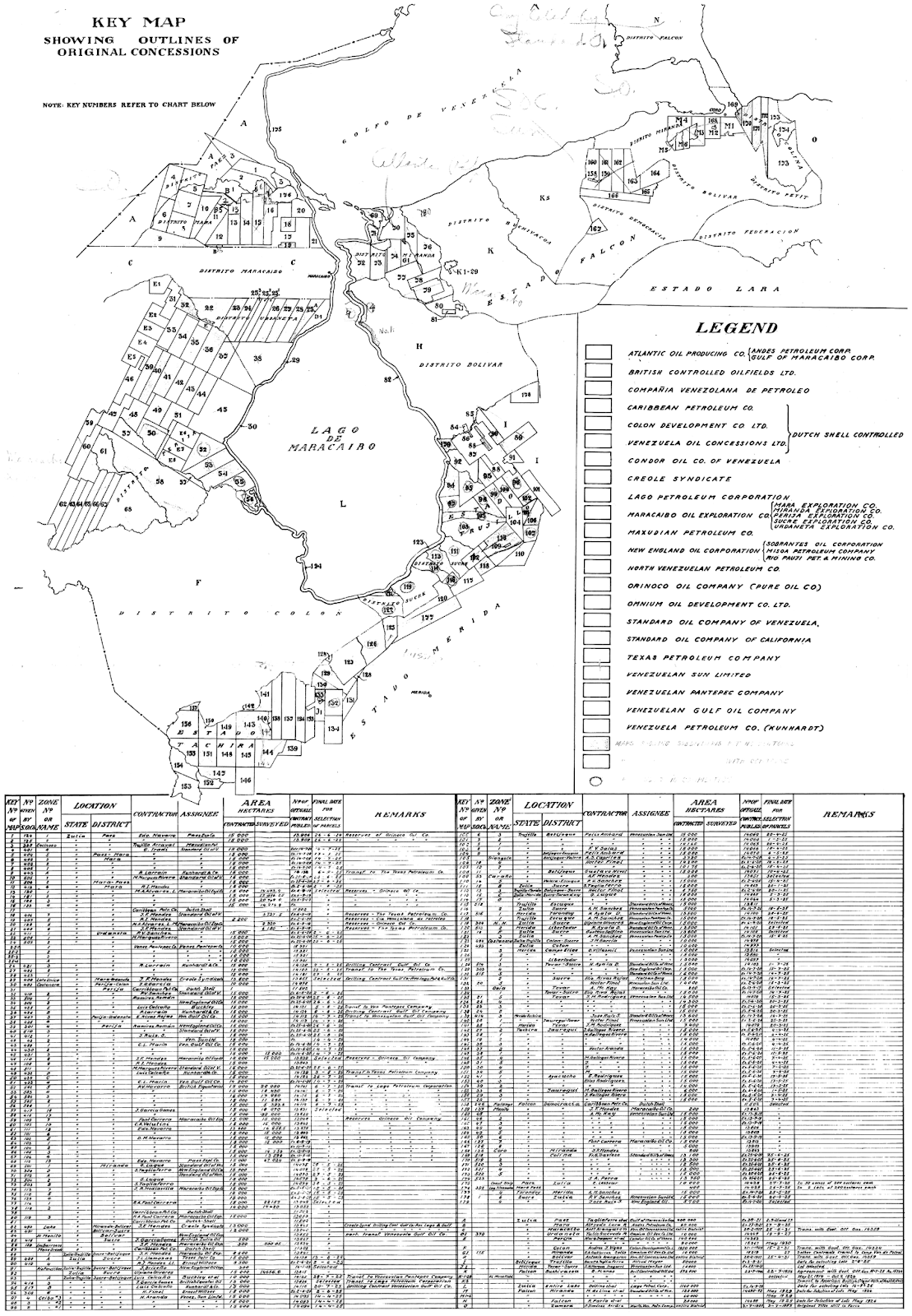

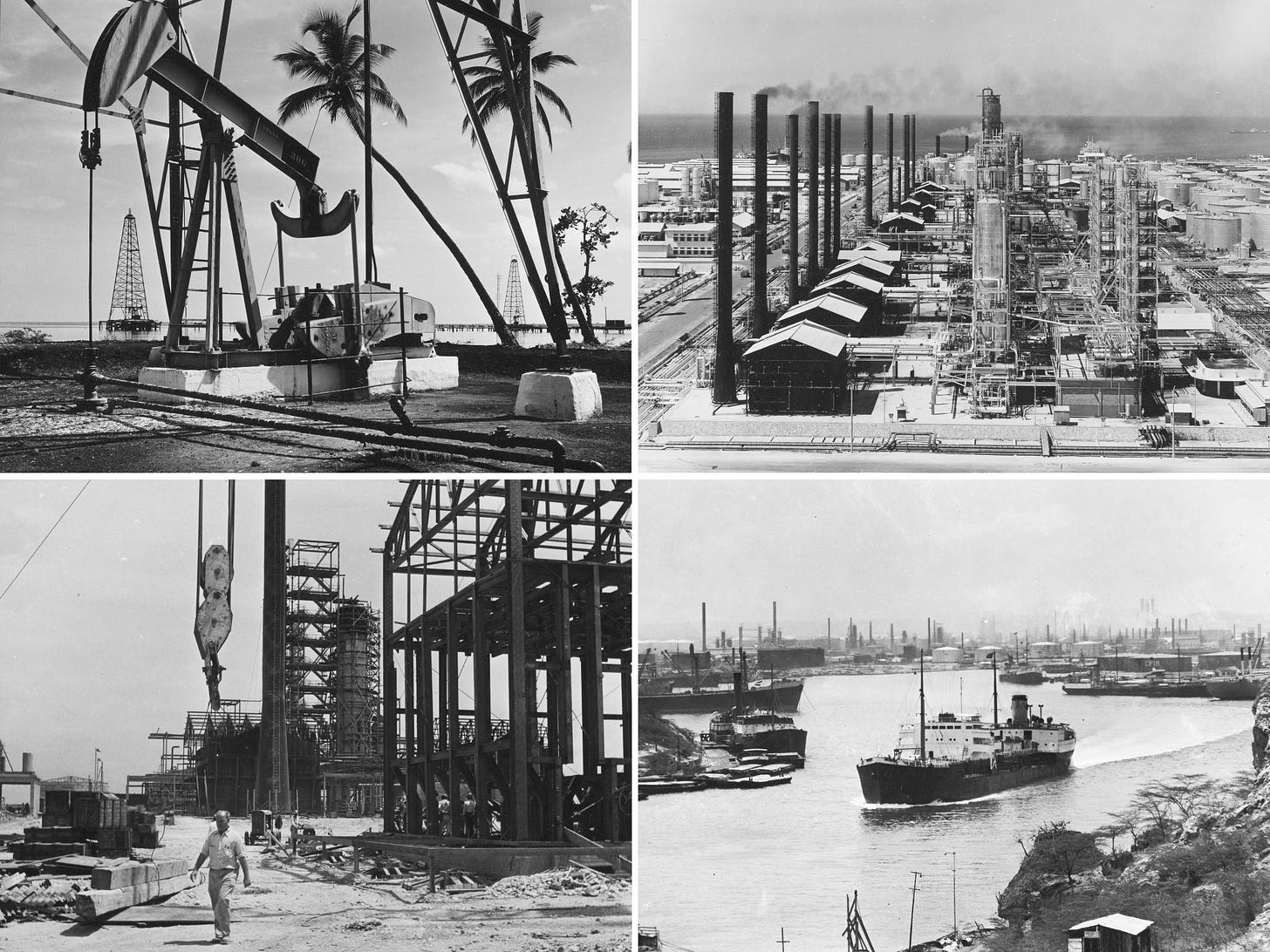

In the United States, the “rule of first possession” and landowner mineral rights encouraged a chaotic proliferation of wildcatters. In Venezuela, the Spanish colonial tradition vested subsurface rights in the state, making petroleum development a matter of administrative concession. American giants such as Standard Oil of New Jersey and Gulf recognized that this centralized ownership structure offered a strategic advantage by providing a single regulatory focal point for negotiation. The Petroleum Law of 1922 marked the consolidation of this bargain. Drafted with direct input from industry representatives, the legislation incentivized a network of regime loyalists who monetized their access by transferring paper rights to foreign firms. The resulting framework was exceptionally accommodating to international capital. It regularized concession rights and structured royalties to ensure Venezuelan oil remained competitive while granting companies wide latitude in their daily operations. Although the subsoil formally remained state property, the law effectively constructed an extractive order where the government served as a passive collector of fiscal rents while strategic control resided entirely with the concessionaires.2 Oil became Venezuela’s most valuable export, and by the 1930s the country was the world’s largest exporter of oil.

Metabolic Rift—Corporate Colonization of Consumption and Agriculture

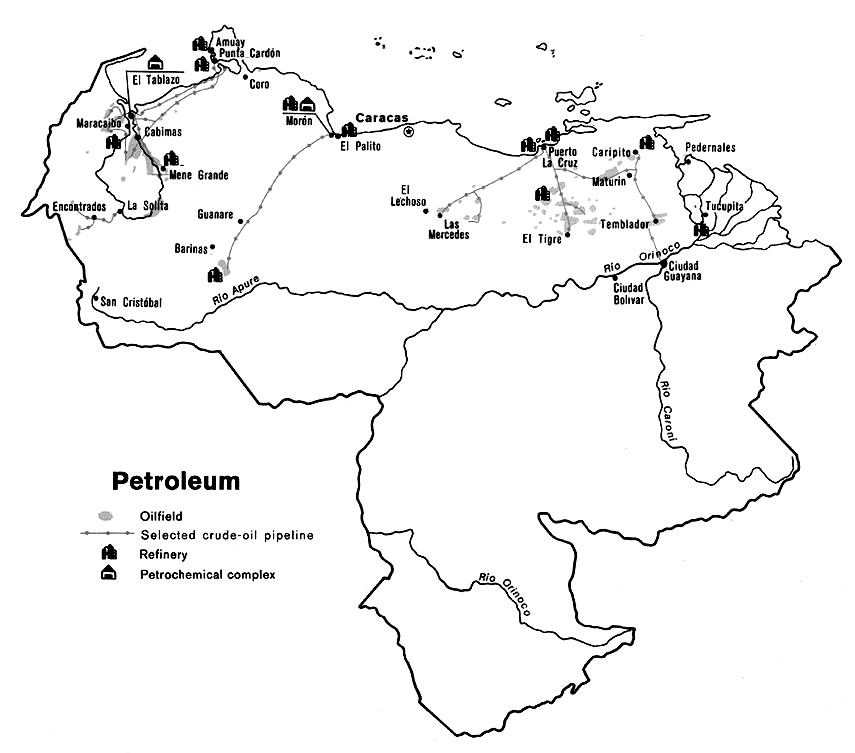

As the legal architecture of extraction solidified, the physical and economic landscape of Venezuela underwent a radical, engineered transformation. The result was the creation of an enclave economy—a sector physically located within Venezuela but economically and legally detached from it. The infrastructure built by Standard Oil (Creole Petroleum) and Shell reflected this extractive logic as pipelines bypassed Venezuelan population centers, and refineries were deliberately constructed offshore in the Dutch Antilles (Aruba and Curaçao) to insulate high-value assets from mainland political instability. This ensured that Venezuela remained an exporter of low-value crude and an importer of high-value refined products, establishing a structural trade deficit in value-added goods that persists to this day.3

The massive influx of petrodollars led to currency appreciation to such a degree that traditional agricultural exports like coffee and cocoa became uncompetitive. By 1935, the agrarian economy had collapsed. The peasantry, displaced from the land and drawn by rumors of wealth, migrated to the periphery of oil camps and cities, forming a nascent urban proletariat that the capital-intensive oil industry could not absorb. However, the colonization of Venezuela in the mid-twentieth century extended far beyond the oil fields; it penetrated the metabolic processes of daily life—how Venezuelans ate, shopped, and moved.

The post-World War II era, characterized by the rhetoric of “modernization,” saw the deliberate dismantling of indigenous economic models in favor of systems requiring constant inputs from U.S. corporations. No figure better embodies this nexus of state power and corporate interest than Nelson Rockefeller. A scion of the Standard Oil dynasty, Rockefeller viewed Venezuela as a laboratory for “enlightened capitalism.”4 Through the Venezuela Basic Economy Corporation (VBEC), established in 1947, he sought to revolutionize the food supply chain in the image of the U.S. While framed as developmental aid as part of a modernization agenda, VBEC served as a mechanism for market capture.

VBEC established the Compañía Anónima Distribuidora de Alimentos (CADA), the first U.S.-style supermarket chain in South America. CADA fundamentally altered the retail landscape, displacing traditional open-air markets that relied on local peasant networks. Because CADA required standardized, mass-produced products that local agriculture could not supply, it turned to imports. By the 1950s, up to 80% of goods sold in CADA were imported from the United States, creating a downstream channel for U.S. agricultural surpluses and socializing Venezuelan consumers into preferring imported wheat and canned goods over traditional staples.5 This transformation extended to the processing of corn, the most basic national staple. The introduction of pre-cooked corn flour (Harina P.A.N.) by Empresas Polar in the 1960s revolutionized the diet but centralized control.6 The industrial process required specific strains of corn and milling machinery imported from the U.S., thus placing the nation’s food security increasingly into the hands of foreign firms.

The inherent volatility of this transition—from agrarian self-sufficiency to urban precarity—demanded a political containment strategy. Venezuelan politics had long been shaped by repeated cycles of military dominance and abrupt regime change, culminating in the fall of the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship in January 1958. With no credible mechanism to arbitrate distributional conflict in an oil-dependent economy, the elite forged the Puntofijo pact. This was the stabilization bargain for the modern rentier state. Its material basis was a class compromise: party elites agreed to share power, while labor and business reached accommodations to secure continuous production. Crucially, U.S. policy reinforced this pact, backing constitutional civilian rule only insofar as it preserved a climate of security for foreign private capital. In practice, Puntofijo institutionalized a rent-mediated order where oil revenues financed political incorporation, masking the deepening dependency.

Under the umbrella of this U.S.-backed stability, the industrialization policy of the 1960s and 1970s, known as “Import Substitution Industrialization,” was effectively captured by U.S. corporations. Automakers like General Motors and Ford established assembly plants in cities like Valencia, but these were not genuine manufacturing hubs. They relied on “Complete Knock Down” kits manufactured in Detroit and shipped to Venezuela for final assembly. This “truncated industrialization” meant that every car “made in Venezuela” actually consumed foreign exchange to import parts.7 Thus, the industrial sector did not reduce dependency on oil; it exacerbated it. By the end of the 1970s, Venezuela had transitioned from a productive agrarian society to a consumption-based society wholly dependent on the U.S. for everything from textiles to the engine blocks in their cars.

Neoliberal Trap—Financialization and the Crisis of Legitimacy

The illusion of prosperity maintained by the Puntofijo order began to fracture as the mechanisms of control shifted from direct corporate ownership of production to the disciplining power of finance. The 1976 nationalization of the oil industry is considered a moment of sovereignty. Yet, while the state assumed legal ownership, operational control remained with transnational firms through “service contracts” and “technology assistance agreements.” The newly formed state affiliates were placed under the new Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), but they still mirrored the old foreign structures,8 ensuring that technological rent continued to flow North even after the physical rent was nationalized. Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, a Venezuelan politician who is considered one of the “fathers of OPEC,” would later call the process a “sham nationalization” (nacionalización chucuta).

Meanwhile, the distributional glue that held the Puntofijo pact together—high oil revenues—began to dissolve as Venezuela moved into the 1980s. U.S. and European banks had aggressively lent recycled petrodollars to the Venezuelan state during the boom years. When U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates in 1979 to combat U.S. inflation (the “Volcker Shock”), the service costs on Venezuela’s variable-rate debt skyrocketed. Combined with a decline in oil prices, this external shock pushed the nation into insolvency.

The ensuing debt crisis was treated less as a commercial bankruptcy than as a geopolitical opportunity. The “Washington Consensus” mandated structural adjustment as the price for bailouts, requiring the dismantling of subsidies, privatization, and trade liberalization. When President Carlos Andrés Pérez began to implement these measures in 1989, the social contract snapped. The Caracazo of February 1989 was a massive popular uprising against the abrupt rise in transport and food prices. The brutal military repression that followed, leaving hundreds dead, delegitimized the existing order and shattered any lingering myth of Venezuelan exceptionalism.

This fragility was exacerbated by the reckless deregulation of the financial sector—a key tenet of the World Bank/IMF program.9 In the early 1990s, the state aggressively liberalized interest rates and relaxed restrictions on foreign participation, yet oversight lagged fatally behind. This regulatory vacuum unleashed a speculative frenzy, as politically connected banks exploited debt arbitrage and “related-party lending” to funnel deposits into their own high-risk ventures. Amidst this institutional decay, Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez led a failed military uprising in February 1992. Although the operation collapsed, the episode propelled Chávez into public view as the most legible antagonist to a discredited political class.

The neoliberal ruling order received its final blow when the banking sector’s house of cards finally collapsed in 1994. Beginning with the intervention in Banco Latino, the state was forced to socialize the losses, paying an exorbitant price to clean up a mess created by private greed while using the crisis as a pretext to denationalize and privatize the financial sector. The crisis stripped the domestic economy of the capital it needed to rebuild and facilitated the flight of wealth abroad. In the aftermath, the hollowed-out Venezuelan banks became easy prey for foreign capital. Under pressure to recapitalize, the government permitted the acquisition of the country’s largest financial institutions by U.S. and Spanish giants like Santander, BBVA, and Citibank.

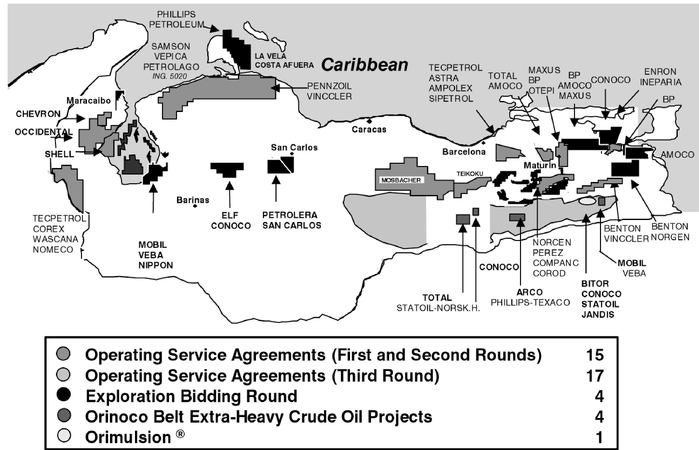

To fill the void left by domestic capital flight, the state accelerated the Apertura Petrolera, or “Oil Opening.” This policy included auctioning operating service agreements (in 1992, 1993, and 1997) and establishing large Orinoco Belt “strategic association” megaprojects—such as Petrozuata, Hamaca, and Cerro Negro—built around upgrading extra-heavy crude for export markets. Designed to lure transnational capital back with the promise of exceptional legal and tax incentives, the state slashed royalties from 16.67% to as low as 1% and cut income taxes from 67.7% to 34%.10 This strategy effectively risked future revenue to secure immediate foreign technology and finance, prioritizing investor returns over the national interest. While it succeeded in raising production, the surge contributed to a market oversupply that crashed oil prices in 1998.11 This economic catastrophe, combined with the deepening corruption scandals of the Puntofijo era, opened the final electoral pathway for an outsider coalition that could plausibly claim to refound the state.

Rupture—Sovereignty, Sabotage, and the Weaponization of Infrastructure

In 1998 Hugo Chávez won the election by a substantial margin. At the outset, the new administration attempted to rewire the fundamental circuitry of how authority and distribution were mediated in Venezuela. Following an antipoverty program, two major reforms were consequential for the coordinated resistance the Chávez government would soon face. First, a new constitution was approved in 1999 by popular referendum which reallocated power away from the party-mediated Puntofijo institutional order and toward a plebiscitary executive armed with new recall and referendum mechanisms, while weakening elite control over institutional chokepoints by redesigning the state around new oversight and electoral authorities that included more of the people. The new constitution also hardened resource sovereignty by reserving petroleum to the state and requiring state ownership of PDVSA, directly threatening the autonomy of the oil technocracy and the contractual expectations of foreign partners. And it constitutionally elevated the state’s directive role in the economy, treating property as protected but explicitly subordinated to “general interest” obligations and social-purpose expropriation, which signaled a more interventionist terrain for land, finance, and investment. Second, The “49 laws” (decree-laws) issued in 2001, were designed to rapidly restructure key domains and avoid legislative bargaining with elite opposition leaders—largely because the reforms represented a frontal assault on the accumulated layers of imperial integration—legal, territorial, and financial—that had been sedimented over the previous century.

A core part of the 49 laws was the Organic Law of Hydrocarbons. This legislation challenged the foundational logic of the 1922 concessions and the neoliberal Apertura of the 1990s. It reasserted state control over upstream activity, limited participation to joint ventures where the state held a majority, and significantly raised royalty rates. In parallel, the Land and Agrarian Development Law targeted the large, idle or uncultivated estates (a 5,000-hectare threshold in specified land classes), while bringing public and private agricultural lands into a regime oriented to national food security planning. This was a direct challenge to the landed property structures that had persisted since the colonial era. These laws did not just annoy the opposition—they threatened the material basis of the elite bargain. The opposition bloc that coalesced in response—comprising business federations (Fedecámaras), traditional unions (CTV), media owners, and the “meritocracy” of PDVSA managers—was united by the existential threat these reforms posed to their integration with global capital.

The institutional response to this reassertion of sovereignty was the coup attempt of April 2002. Declassified U.S. intelligence reporting from April 6, 2002 described “conditions ripening for coup attempt,” indicating that dissident military factions were stepping up efforts and might act within the month, and that plotters could try to exploit unrest from planned opposition demonstrations to provoke military action, with scenarios including detaining Chávez and key officials. When the interim government of Pedro Carmona briefly seized power for 47 hours in April, their first move was to dissolve the Supreme Court and the National Assembly and, crucially, to nullify the 49 Laws, revealing the true nature of the coup: a restorationist project designed to reset the rules of accumulation and re-secure the oil rent channel for the old elite.

However, the failure of the coup led to a so-called Paro Petrolero, or “Oil Strike,” of 2002–2003. It was during this conflict that the weaponization of the technological stack was first fully deployed, and the contours of the U.S. digital surveillance apparatus during the Bush administration took shape. This is covered in Part II.

Notes

Paine, Thomas. 1974. The Life and Major Writings of Thomas Paine. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press: 400.

On this saga, see: McBeth, B. S. 1983. Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935. Cambridge University Press.

Earlier scholarship on “unequal exchange” provided a broad outline of this sort of trade relationship: Raul Prebisch, The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems (United Nations, 1950); Emmanuel Arghiri, Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade (Monthly Review Press, 1969).

Rivas, Darlene. 2002. Missionary Capitalist: Nelson Rockefeller in Venezuela. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Hamilton, Shane. 2018. “Supermercado USA.” In Supermarket USA: Food and Power in the Cold War Farms Race, 70–96. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Felicien, Ana, Christina Schiavoni, and Liccia Romero. 2018. “The Politics of Food in Venezuela.” Monthly Review 70 (2). https://monthlyreview.org/articles/the-politics-of-food-in-venezuela/.

Coronil, Fernando, and Julie Skurski. 1982. “Reproducing Dependency: Auto Industry Policy and Petrodollar Circulation in Venezuela.” International Organization 36 (1): 61–94.

For example Lagoven was the old Creole/Exxon and Maraven was the old Shell.

For more details, see the 1995 Project Completion Report: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/502991468315002614/pdf/multi-page.pdf.

Mommer, Bernard. 1998. “The New Governance of Venezuelan Oil.” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/WPM23-TheNewGovernanceOfVenezuelanOil-BMommer-1998.pdf.

Boué, Juan Carlos. 2013. “Conoco-Phillips and Exxon-Mobil v. Venezuela: Using Investment Arbitration to Rewrite a Contract.” Investment Treaty News, September 20, 2013. https://www.iisd.org/itn/2013/09/20/conoco-phillips-and-exxon-mobil-v-venezuela-using-investment-arbitration-to-rewrite-a-contract/.

I only knew a few parts of this. Impressive recounting of events. Looking forward to part 2!

Wow! Thank you for this informative piece of work. I can't wait for the next extract of the US in Venezuela.