The United States in Venezuela II—How to Sabotage an Oil State

How outsourcing Venezuela’s technological infrastructure established the blueprint for weaponized interdependence

The failed 2002 coup in Venezuela was quickly succeeded by a more insidious form of sabotage via networked infrastructure. This episode starkly revealed the vulnerabilities inherent in the commercial interdependence that binds global corporate networks today. However, to understand how these infrastructural ties—originally designed to bind nations together—became weapons of coercion, we must return to their ideological origins. Let’s briefly revisit the “pacific system” of commerce from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (see Part I for an introduction). This concept, which served as a precursor to the Monroe Doctrine, rested on the premise that peace could be secured through institutions and incentives rather than warfare. However, in espousing the pacific system, the American founders also harbored explicit aims to craft new governing arrangements across the hemisphere in the image of the United States (a government of powerful merchants, lawyers, and property owners). Writing in the immediate wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, and during the height of the Latin American wars of independence, William Thornton—the architect of the U.S. Capitol—identified the inherent risks of this pacific ambition in his 1815 text Outlines of a Constitution for United North and South Columbia. He proposed a hemispheric confederation across the Americas precisely because he feared that if the republic could not ensure its hegemony, the pursuit of peace would signal weakness and invite predation:

[I]f governments form themselves around us, essentially different; if daring chiefs, at the head of armies, and ambitious politicians, disturb our repose, it will be vain to offer the branch of peace. Our pacific system, if continued, would then but offer temptations to aggression, and we should repine at the necessity of armies and warfare, now so justly deprecated.1

Thornton also feared that the vast internal distances of the continent would turn administrative delay into political fragmentation. He argued that the government must act with speed to avoid offering temptations to aggression. The emerging technology of the telegraph offered a solution to this dilemma by compressing territory into governable time. Thornton marveled that “intelligence can now be given with ease twenty miles a minute.” Once perfected, he believed telegraphs could “convey from the remotest bounds of this vast Empire, any communication to the supreme government” and enable measures to be taken “as rapid as the occasion may require.”2 In theory, it allowed the state to secure unity and responsiveness without defaulting to the permanent militarized presence that the pacific ideal sought to avoid. Networked communication technologies were thus viewed from the outset (~200 years ago) as critical to command and control. It also enabled a new form of corporate power by coordinating the transnational geography of early oil companies, and today, serves as a key mechanism of imperial control.

This essay, Part II, explores how U.S. actors deployed these technologies when Hugo Chávez attempted to reform the Venezuelan oil economy. Chávez certainly embodies Thornton’s figure of an “ambitious politician disturbing the repose” of the United States. His anti-neoliberal Agenda Alternativa Bolivariana platform aimed to dismantle the established Puntufijo order and restructure the political system to be more democratically responsive. He argued that while oil must remain the productive core of the nation, the then-existing export model (Apertura Petrolero) entrenched a quasi-colonial dependency. To cure this, he proposed a strategy of re-nationalization and sovereign industrialization. This approach prioritized domestic scientific development to rebuild national power rather than yielding to transnational capture.3 He articulated this long-term vision clearly at his inauguration:

The economic battle, the transformation of the economic model, and the building up of productive economic activities to move away from the oil-dependent rentier model is a challenge that lies before us.4

The 2001 Hydrocarbon Organic Law served as the opening salvo of this agenda, but it immediately triggered a coup and sabotage campaign designed to topple his administration. This event is quite useful for understanding the trajectory of U.S. intervention in Venezuela. It provides the historical blueprint for the weaponization of networked technologies, a tactic that has since evolved into the more robust system of “weaponized interdependence” visible today.5

Trojan Horse—The Intesa Affair and the Meta-State

The events that transpired in Venezuela between December 2002 and February 2003 constitute a watershed moment in the history of technological warfare and state sovereignty. The “Oil Strike” of December 2002 may easily be misunderstood as a labor dispute or a civic protest (as the name evokes). In reality, it was a management lockout combined with a sophisticated technological sabotage operation—a kinetic assault on the nation’s economic foundation. Oil production collapsed precipitously from three million barrels per day to less than 25,000. For the first time in the digital age, a sovereign nation’s primary economic engine, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), was brought to a near-total standstill not by external military bombardment, but by the weaponization of its own information technology infrastructure. This paralysis demonstrated to the Chávez government that sovereignty over natural resources is meaningless without sovereignty over the technology used to extract them.

To understand how the Venezuelan state was locked out of its own industry, one must understand the management architecture of the Apertura Petrolera of the 1990s (also introduced in Part I). Aside from looking for foreign investment, this policy introduced new management philosophies within PDVSA itself, forming a group known later as the “Meritocracy.” This faction was led by figures such as Luis Giusti—then-CEO of PDVSA who later became a key outside architect of the Bush administration’s National Energy Policy during the 2000–2001 transition. Under this leadership, the Meritocracy operated as a ‘meta-state’: a powerful corporate bureaucracy that functioned with near-total autonomy from the central government.6 They advocated for the internationalization of the industry, which in practice meant the privatization of non-core functions and the adoption of corporate structures that mirrored multinational oil giants rather than state-owned enterprises. The logic was that information technology was just a commodity to be purchased—a support service rather than a strategic asset to be guarded. Prior to 1996, PDVSA’s IT landscape was fragmented, consisting of disparate systems that the management sought to standardize for efficiency. This drive for standardization provided the rationale for a massive outsourcing project that would ultimately place the keys to the kingdom in foreign hands.

In 1997, this strategy materialized with the creation of INTESA (Informática, Negocios y Tecnología, S.A.). This joint venture was established to manage the entirety of PDVSA’s information infrastructure, from help desks to complex reservoir modeling systems. However, the equity structure was critically unbalanced: 60% was owned by Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) and only 40% by PDVSA. This split effectively transferred decision-making power and technical control of Venezuela’s most critical infrastructure to a foreign entity.7 By 2000, INTESA managed nearly all of PDVSA’s data processing and transmission, creating a monopoly on the flow of information within the company.

The selection of SAIC as the majority partner remains the most contentious and revealing aspect of this arrangement. SAIC was not a standard commercial IT provider like IBM. It was, and remains, a primary contractor for the United States national security apparatus. SAIC’s leadership was heavily populated by former intelligence officers from the NSA, CIA, and the Department of Defense, with deep ties to the development of information warfare capabilities. By handing over its IT infrastructure to a firm embedded in the “Deep State” of a foreign power—one that would soon become hostile to the Bolivarian Revolution—PDVSA’s pre-Chávez management effectively placed the country’s economic nervous system under the influence of the U.S. imperial apparatus.

This transfer was not just administrative—it had material and cultural elements too. Approximately 1,600 PDVSA IT employees were transferred to INTESA, where they were subjected to a deliberate reshaping of their professional identity. The bureaucratic culture of the state oil company was replaced with a Silicon Valley mentality that emphasized stock ownership in the parent company. SAIC implemented an “Employee Stock Ownership Plan” (ESOP), and by 2002, 88% of INTESA personnel held stock in the U.S. defense contractor.8 This financial entanglement created a fatal conflict of interest. Many IT workers identified more with transnational corporate objectives than with the national mandate of the new Venezuelan government. When the political order came down to execute the strike, the “brain” of PDVSA had already been privatized, not just technically, but ideologically.

Black Box—Anatomy of a Cyber-Sabotage

Juan Fernández served as the visible face of Gente del Petróleo, coordinating the public spectacle of the strike, its effectiveness relied entirely on the covert maneuvers of the INTESA workforce. As Fernández declared political victory in press conferences, the technicians behind the scenes were executing the digital lockouts that made the stoppage a reality. This sabotage was made possible by the weaponization of the very infrastructure INTESA had built for efficiency; the centralization of the network transformed it into a mechanism of control through the “black box” phenomenon. Because INTESA retained exclusive possession of proprietary codes and administrative privileges, the Venezuelan government found itself locked out of its own industry. A rogue team of high-level administrators exploited their root access to dismantle the system from within, shutting down servers, changing passwords, and disabling remote access to ensure that the state remained paralyzed.

The sabotage was executed through a sophisticated combination of physical and digital vectors. Saboteurs installed hidden modems in walls and false floors to bypass physical security, allowing them to control and shut down systems from remote locations. They modified access keys and user privileges to physically lock loyalist engineers out of the digital systems required to run the plants. Crucially, they attacked the Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems that monitor pressure, flow, and temperature in pipelines and refineries. By blinding operators to critical safety data, they created the risk of over-pressure events and explosions, effectively holding the physical infrastructure hostage.9

The most crippling aspect of the offensive was the “total and unexpected collapse” of the SAP system.10 PDVSA had migrated its entire administrative, financial, and logistical workflow to SAP under INTESA’s guidance. This software managed everything from the procurement of spare parts to the generation of bills of lading for supertankers. When INTESA cut access, the blackout was absolute. PDVSA could not issue invoices for oil exports, meaning that even if oil could be physically loaded, it could not legally be sold under international maritime law. The company was unable to process Value Added Tax declarations, leading to a legal crisis with the national tax authority.11 Logistical automated systems for spare parts went offline, forcing operators to cannibalize machinery to keep refineries running. Critical databases containing historical geological data were erased or encrypted, permanently damaging the management of high-pressure extraction environments.

The recovery of PDVSA, mythologized in Venezuelan political culture as the Rescate del Cerebro (Rescue of the Brain), was a desperate, improvised operation involving loyalist engineers, the National Armed Forces, and volunteer IT specialists. Resistance was led by a cadre of professionals who refused to join the strike, such as Socorro Hernández, who coordinated a team of “patriotic technicians” and hackers. Their strategy was multi-pronged. The National Guard physically occupied INTESA offices to prevent the destruction of hardware, while a collective of Venezuelan hackers worked around the clock to crack administrative passwords, boot servers into single-user modes, and reconstruct corrupted partition tables. In the absence of automated systems, retirees and volunteers operated refineries manually, physically turning valves and calculating flow rates with pencil and paper—a highly risky process that saved the industry from total collapse.12

The devastation was nonetheless immense. Official estimates place the direct economic losses between $14 billion and $20 billion. For the first time in its history, Venezuela ran out of gasoline, forcing the government to import fuel to keep food and medicine moving. The abrupt shutdown of wells caused irreversible damage to reservoirs in Lake Maracaibo, permanently reducing production capacity. In the aftermath, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice ruled that INTESA’s actions constituted a deliberate violation of the constitution, noting that the company had withheld data for “purely political reasons.”13 This legal battle confirmed what the government already knew—that the “meritocracy” had prioritized political damage over the preservation of the assets they claimed to protect.

The U.S.’s Overseas Private Investment Corporation (a federal agency that provided political risk insurance and development finance, later reorganized into the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation) explicitly rejected the defense that INTESA sabotaged PDVSA’s infrastructure, determining that the seizure of assets and operational control constituted a “total expropriation” by the state. It ruled that the takeover was uncompensated and confirmed that SAIC qualified for a payout under its insurance contract. PDVSA responded days later by demanding independent international arbitration. Thomas Wilner, the company’s counsel at Shearman & Sterling, dismissed the ruling as a political maneuver arguing that the decision ignored the facts to appease a corporation with powerful connections to the Bush administration.

Siege of Hardware—From Sabotage to Sanctions

From the ashes of the INTESA affair, the government institutionalized the rescue effort within a new internal department known as AIT. Staffed by the loyalists and volunteers who had saved the industry, this unit focused on stabilizing recovered systems and decoupling PDVSA from foreign contractors. The trauma of the shutdown drove a radical shift in state strategy as officials recognized that proprietary software was a black box that could hide backdoors or be revoked by external powers. President Chávez signed Decree 3390 in 2004 to mandate the use of free and open-source software across the public administration in an effort to eliminate the technological rent paid to U.S. corporations. The state launched projects like the Canaima GNU/Linux distribution to socialize a new generation away from Silicon Valley norms, and this quest for independence soon extended to physical infrastructure. By 2007, the government nationalized strategic sectors and partnered with China to launch satellites in an attempt to construct a technological stack immune to Washington’s kill switches. Yet implementation struggled to match this ambition. By 2013, AIT workers were still warning that a deepening dependence on proprietary systems like SAP compromised sovereignty. They argued that externalizing control over core commercial operations merely recreated the vulnerability of the Intesa era by handing expertise and access back to foreign vendors.14

While Venezuela made efforts to migrate its software, it still remained trapped by its hardware. Following the death of Chávez in 2013 and the subsequent collapse in oil prices, the U.S. strategy shifted from covert sabotage to overt economic warfare. The sanctions regime, particularly under Trump 1.0 (2017–2021), transformed the global supply chain into a weapon of mass destruction. As one official from the State Department put it:

The pressure campaign is working. The financial sanctions we have placed on the Venezuelan Government has forced it to begin becoming in default, both on sovereign and PDVSA, its oil company’s, debt. And what we are seeing because of the bad choices of the Maduro regime is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. So our policy is working, our strategy is working and we’re going to keep it on the Venezuelans.

The phrase “bad choices” invites a dual reading. While it overtly serves the propaganda narrative of administrative incompetence, it simultaneously operates with the cynical logic of a protection racket—implying that the regime’s fatal error was simply its refusal to capitulate to external demands, thereby forcing the US to inflict the damage. Meanwhile, the impact of sanctions on Venezuela’s infrastructure was fundamentally technological while its consequences spread to the nearly entire population. Modern infrastructure relies on a continuous stream of proprietary spare parts and updates from original equipment manufacturers, most of whom are U.S. or European firms like General Electric and Siemens.

Executive Order 13884, issued in 2019, induced a state of “overcompliance” in the global compliance departments of major corporations. Fearing U.S. Treasury penalties, these companies severed all links with Venezuela, creating a “technological embargo.” Adobe announced it would deactivate all accounts in Venezuela to comply. Oracle followed suit and threatened the database operations of Venezuelan banks and insurance firms.

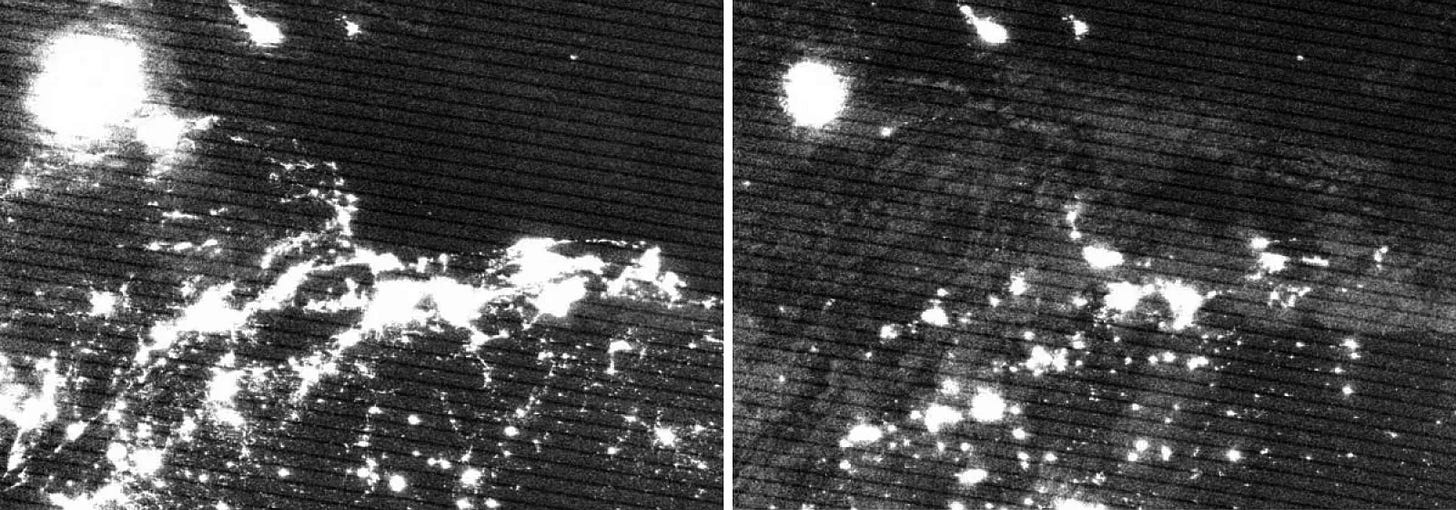

The decay of the electrical grid provides the starkest example of technological warfare. Venezuela’s thermal power plants run on turbines that require proprietary parts and service contracts. Unable to purchase these, the state was forced to cannibalize machines, drastically reducing thermal generation capacity and forcing dangerous over-reliance on the Guri Dam’s hydroelectric output (which provides ~75% of Venezuela’s power). When the Guri transmission lines failed in March 2019, plunging the country into a massive, multi-day blackout, there was no thermal backup to stabilize the grid. While the government alleged a U.S. cyber-attack on the Guri’s SCADA systems—a plausible scenario given the vulnerability of legacy systems to cyber-physical attacks—the collapse could have been indirectly attributable to sanctions-induced decay. The timing of the blackout, coinciding precisely with the U.S.-backed attempt to install Juan Guaidó as interim president, and the immediate, detailed commentary from U.S. officials, suggested a coordinated campaign where infrastructure failure was weaponized to delegitimize the Maduro government.

(Left) Satellite view around Caracas, Venezuela, March 3, 2019. (Right) Satellite view of blackout around Caracas, Venezuela, March 8, 2019. Source: NASA.

Digital Enclosure and the Lawfare Machine

The INTESA episode serves as a historical prologue to a far more pervasive form of containment that has coalesced in recent years. This earlier intervention produced a reactive dialectic in which the Venezuelan state sought to secure its internal survival through alternative dependencies. Yet the struggle for sovereignty is not confined to the digital infrastructures of hybrid warfare—the legal domain remains a critical layer of the imperial “full stack.” A significant portion of the resource conflict has unfolded within arbitration panels and legal tribunals over the very sites where the architecture of the oil empire was first codified.

Major players that departed following the end of the 1% royalty rate during the Chávez era pursued international arbitration to seize or monetize Venezuelan-linked assets abroad. Beginning in 2007, firms like ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil utilized these legal claims to create pressure. More recently, the litigation surrounding Citgo illustrates how arbitration enforcement transforms into asset seizure. Crystallex sought to collect a roughly 1.2 billion dollar award by attaching the United States holding company chain of PDVSA that owns Citgo. The courts facilitated this by treating the state oil company as the “alter ego” of the Venezuelan government. That ruling triggered a court-supervised auction in November 2025 of the shares held by PDV Holding. A judge approved a bid of roughly 5.9 billion dollars by Amber Energy which is owned by Elliott Management and led by Paul Singer. While the sale remains pending due to Office of Foreign Assets Control clearance and appeal processes regarding alleged conflicts of interest, the legal system still serves as the initial mechanism of dispossession.

Washington has since constructed a lattice of oversight around Venezuelan commodities that operates in tandem with these judicial maneuvers. Through sanctions and licenses, the United States permeates the global plumbing of trade and influences the movement of capital and cargo through banks, insurers, and shipping registries. This complex regime effectively determines who is allowed to interact with Venezuelan wealth. It shapes the rules and chokepoints of global logistics so that control over finance becomes the primary method to steer physical resources. Combined with technological sovereignty pursued since the early 2000s, the resulting economic asphyxiation creates a desperate domestic environment that forces the Venezuelan state to seek technological lifelines elsewhere. The government moved to weaponize digital tools for social control and utilized the Carnet de la Patria system to track beneficiaries of social programs—built with Chinese technology provided by ZTE. In other domains too, the state continues to shift its technological reliance from the United States to China and Russia in a bid to construct a parallel stack.

The resilience of this new architecture was tested in December 2025 when PDVSA faced a U.S. blockade alongside a coordinated cyberattack intended to paralyze operations. The true extent of the damage remains ambiguous. Juan Fernández of Gente del Petróleo argued that the industry is effectively blind and unable to endure the pressure because of deep logistical and financial voids. Venezuelan cybersecurity specialists rebuffed such claims and criticized the actions as a militarized campaign of denial-of-service distractions and targeted intrusions that echoed the sabotage of 2002. Whether the attack successfully penetrated the core of this new sovereign stack or was repelled by it remains an open question in a conflict now fought over server access and software protocols.

This technological and financial siege produced a profound social consequence that fed back into the machinery of American power. The economic collapse precipitated by sanctions created a desperate labor pool. As the bolívar lost its value, large numbers of Venezuelans turned to precarious data work.15 They performed image and video labeling, content moderation, and categorization through platforms that supply training data to major vendors like Scale AI (owned by Meta). Hao and Hernandez tell the story of a Venezuelan college student who prepared for a well-paid job in the oil industry but had to switch to full-time AI training when the economy collapsed. Venezuelans formed an unusually large share of the annotator workforce around 2018 and comprised up to 75% of the labor at firms servicing computer-vision pipelines which rely on microtasks that pay only cents per label.

In the years spanning 2024 and 2025, the Pentagon effectively industrialized this supply chain. AI was paid at massive scale to turn raw data into “AI-ready” training and evaluation services for the military while GenAI.mil pushed frontier models from Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI into military networks with the aim of being deployed for intelligence triage, operational planning, and targeting. In effect, the low-wage annotation economy reappears downstream as the perceptual substrate of surveillance and targeting. The everyday classification of objects helps military systems identify what constitutes a radar or air defense site from satellite or airborne imagery. In this sense, the concept of digital enclosure encompasses more than just sanctions, tribunals, and server access. It describes how imperial power routinizes human poverty into training data and then routinizes that data into the capacity to see, classify, and strike.

Perhaps the bombing and abduction of the Venezuelan President in January 2026 may be seen in a new light—certainly an escalation—a contingent conjuncture at the center of these converging systems rather than a definitive endpoint. The degradation of infrastructure through sanctions and the delegitimization of sovereignty through arbitration aimed to weaken the target long before troops landed. The possible use of AI-enhanced military capacities played a distinct role in these kinetic operations. The argument that Venezuela had stolen American assets was an inversion of reality. After decades of weaponizing software, banking codes, sanctions, and legal measures to asphyxiate the country, the so-called “Donroe Doctrine” simply migrated into the battlefield. Yet, such overt violence may reveal the weakness in the American imperial project rather than its strength.

This case has offered a stark warning to the Global South regarding the reality of weaponized interdependence. It demonstrates that national sovereignty is impossible without technological autonomy and robust military capacity. Ownership of the subsoil effectively means nothing if a hostile power owns the code that runs the extraction machinery and dictates the laws of commerce. The tragic irony is that this persistent conflict with the United States has only calcified the status of Venezuela as a petro-state and trapped it within the very extraction model it sought to escape—a victory for fossil capital. Ultimately, the January 2026 incursion simply makes the underlying geopolitical logic more visible. It is an attempt to preserve a global power structure that remains fatally tethered to fossil energy.

Notes

William Thornton, “Thornton’s Outlines of a Constitution for United North and South Columbia,” Hispanic American Historical Review 12, no. 2 May 1932: 206.

Ibid.: 214.

Chávez, Hugo. 1996. Agenda Alternativa Bolivariana. Caracas, Venezuela: Ediciones Correo del Orinoco.

Translation mine, from the original: “[L]a batalla económica, la transformación del modelo económico, levantar las actividades económicas productivas para ir saliendo progresivamente del modelo rentista petrolero, es un reto que tenemos por delante.” Hugo Chávez, speech at his inauguration as President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela for the period (2000-2006), Legislative Palace, August 19, 2000.

Farrell, Henry, and Abraham Newman. 2023. Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy. Henry Holt and Company.

Ibañez, Pedro. 2012. “2 de Diciembre: A Diez Años Del «paro Petrolero», Sabotaje Criminal de Una Meritocracia Contra El Pueblo [December 2: Ten Years after the ‘Oil Strike’, a Criminal Act of Sabotage by a Meritocracy against the People].” United Socialist Party of Venezuela. December 2, 2012. http://www.psuv.org.ve/portada/2-diciembre-diez-anos-paro-petrolero-sabotaje-criminal-una-meritocracia-contra-pueblo/.

Sánchez, Eleazar Mujica. 2025. “A 50 Años de una Traición Petrolera (Parte III) [50 Years After an Oil Betrayal (Part III)].” Intersaber, September 28. https://intersaber.org/2025/09/28/a-50-anos-de-una-traicion-petrolera-parte-iii/.Velutini, Magdalena, and Robert Bottome. 2002. “Rechazando el éxito: El increíble caso de Intesa [Rejecting success: The incredible case of Intesa].” VenEconomía Hemeroteca 20 (1). https://luiscastellanos.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/09/veneconomia-rechazando-el-exito-caso-intesa.pdf.

See Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel. Del Terrorismo Petrolero al Golpe Económico [From Oil Terrorism to the Economic Coup]. Reported in Toledo, Yuleidys Hernández. 2024. “Tellechea es vinculado con empresa involucrada en golpe contra Hugo Chávez [Tellechea is linked to a company involved in the coup against Hugo Chávez].” DiarioVea, October 22, 2024. https://diariovea.com.ve/tellechea-es-vinculado-con-empresa-involucrada-en-golpe-contra-hugo-chavez/.

See Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel. Del Terrorismo Petrolero al Golpe Económico [From Oil Terrorism to the Economic Coup]. Reported in Toledo, Yuleidys Hernández. 2024. “Tellechea es vinculado con empresa involucrada en golpe contra Hugo Chávez [Tellechea is linked to a company involved in the coup against Hugo Chávez].” DiarioVea, October 22, 2024. https://diariovea.com.ve/tellechea-es-vinculado-con-empresa-involucrada-en-golpe-contra-hugo-chavez/.

Translation mine. Seventh Superior Contentious Tax Court of the Judicial District of the Metropolitan Area of Caracas, Final Judgment No. 1740 (Caracas, June 30, 2014), case AP41-U-2004-000102. https://caracas.tsj.gob.ve/DECISIONES/2014/JUNIO/2101-30-AP41-U-2004-000102-SENTENCIADEFINITIVAN%C2%BA1740.HTML.

Ibid.

A detailed account is available in: Albarrán, Franklin, Samuel Carvajal, Carmen Chirinos, Maryann Hanson, Carlos M. Mujica, Haydee Nava, Eric Omaña, Carlos Polanco, and Tibisay Hung. 2013. Testimonios del rescate de PDVSA [Testimonies of the Rescue of PDVSA]. Caracas, Venezuela: Fondo Editorial Ipasme. http://ipasme.gob.ve/images/Varias/Fondo%20Editorial/Ciencias%20Humanas/Coleccion%20contra%20el%20Olvido/Libros/testimonio%20PDVSA%20TOMO%20I.pdf.

Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (Venezuela), Decision No. 827 (May 6, 2004). Cited in Seventh Superior Contentious Tax Court, Final Judgment No. 1740.

Roa, Luigino Bracci. 2013. “Trabajadores de PDVSA Rotundamente Opuestos a Que Empresa Alemana SAP Controle Sus Sistemas Informáticos.” Blogger. October 28, 2013. https://lubrio.blogspot.com/2013/10/trabajadores-de-pdvsa-rotundamente.html.

Posada, Julian. 2024. “Deeply Embedded Wages: Navigating Digital Payments in Data Work.” Big Data & Society 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241242446.

---

Many people describe Maduro and his government as dictatorial, cruel, and thuggish. I believe that Venezuela, ever since Chávez nationalized oil—taking it away from American companies and consequently being accused of communism and anti-Americanism—has been subjected by the United States to total economic sabotage, including an embargo on its oil exports and on its ability to repair and modernize its extraction industry. Clearly, this situation has led to an economic collapse worse than the one that existed when American companies were siphoning off most of the oil revenues from the nation. As everywhere, destitution produces popular discontent and, in the long run, also acts of unrest and rebellion. We are seeing this now in Iran as well, which—rightly or wrongly—is undergoing a severe economic crisis due to sanctions. The tactic of starving a state because it defies U.S. dictates, or worse because it is communist, has been applied to Cuba for over 60 years. But if they are communists, isn’t that their own business? Khrushchev’s missiles are no longer there.

Therefore, governing a population anguished by poverty is certainly not easy using democratic methods, and if one wants to keep the commitment not to give in to American blackmail, one must also adopt harsh and despotic measures. Or does anyone really believe that, in a state of war—if not military, then certainly economic war—it is possible to govern with a light hand and not suspect saboteurs and traitors collaborating with the enemy here and there? As for the idea that the majority of the Venezuelan people wish to disavow Chávez’s course of action and once again place their oil in American hands, whatever the wealth it may represent, I do not believe there is any objective evidence of this. The gringos have never been popular in South America, except with a few people with vested interests, such as Machado (once upon a time, anyone who called for foreign intervention in their own country was labeled a renegade, but opinions today are very elastic—and the Nobel Prize proves it).

Until Chávez came to power, the situation was characterized by “disastrous socio-economic conditions for the vast majority of Venezuelans.” “Malnutrition affected 21% of the population in 1998” (Wikipedia).

It was not the nationalization of the oil industry that impoverished Venezuela—which was instead exploited by extraction companies—but the boycott to which it was subsequently subjected.

Personally, I am more inclined to believe experts on the subject who say that cocaine trafficking from Venezuela is far lower than that from Colombia and Mexico. But even if the opposite were true, I believe it would have been a justified retaliation against the U.S. economic war: *à la guerre comme à la guerre*. If someone tries to strangle you by grabbing you by the throat, it is only natural that you will try to kick them in the balls.

In any case, one only needs to look back at history to see that every time U.S. economic interests are challenged, the same script is repeated. Mossadegh got off more lightly—he was neither kidnapped nor imprisoned. Who still remembers Mossadegh, who tried to take Iranian oil out of the hands of the Seven Sisters? Then came the Shah, and then the ayatollahs; perhaps it would have been better to let Mossadegh proceed.

Mattei, head of Italy’s ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi), for having stepped on the toes of the Seven Sisters who wanted everything for themselves, was brought down in a plane crash that has never been fully explained.

Not a leaf moves unless Uncle Sam wants it to—inevitably, given the enormous military power he deploys. But in the meantime, a quarter of GDP is spent on armaments, the debt has grown so large that some have begun exchanging bonds for gold and silver, which have reached record highs. Will the hegemony of the dollar last longer than its armed forces?

---