The Structural Violence of Risk Management Behind the AI Infrastructure Bubble

How financial institutions sustain the AI boom by exporting risks to everyone else

On November 5, 2025, OpenAI CFO Sarah Friar suggested in a public talk that she hoped the federal government would help support future AI infrastructure investments, remarks that many interpreted as a call for a government “backstop” on the company’s roughly $1 trillion in planned data-center deals (think “too-big-to fail” logic). After a wave of critical coverage and market anxiety, Friar walked back the wording and CEO Sam Altman went further, posting that OpenAI neither has nor wants any government guarantees for its data centers, insisting that taxpayers should not bail out failed companies. The comments were aimed at securing “frontier chip” technology the company sees as instrumental in pushing ahead (see some background into this issue in a previous post). Yet, his assertion of private-sector responsibility, offered at a moment when AI stocks like Nvidia and Palantir were selling off on fears that AI spending has outrun profits and market stability, underscores a core tension in AI finance. The sector rests on enormous, interlocking infrastructure commitments and circular investment flows, coupled with an ongoing search for someone else to hold the downside risk (that’s all of us).

Boom or bubble—the real question is who pays?

Across the world, banks are financing the physical architecture of artificial intelligence—rows of energy-hungry data centers, chip fabrication plants, and new corridors of power and water to keep them running. The scale is staggering. A single facility can draw as much electricity as a mid-sized city. Yet even as they accelerate the build-out, banks are already seeking protection from the risks of the very boom they have helped create.

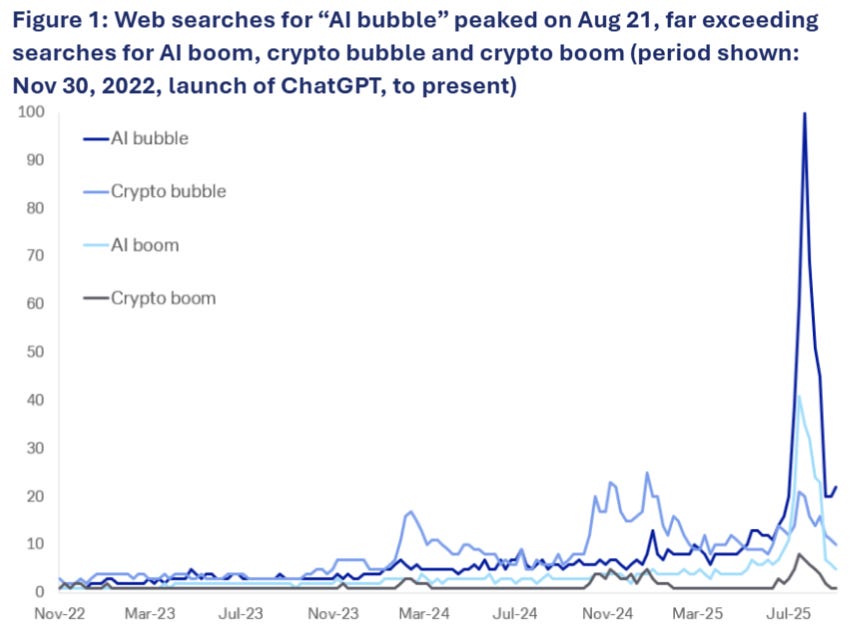

In September 2025, Deutsche Bank published a research note titled “AI Bubble Bubble Bursts.” The report suggested that fears of an AI bubble had themselves popped. Google searches for the term had plunged, media coverage had cooled, and investors had apparently regained confidence. The authors argued that bubbles are nearly impossible to define and that hype often softens into another phase of expansion rather than a crash. They conceded that AI’s growth faces constraints—mounting costs, limited energy supply, and the slow pace of corporate adoption—but framed these as technical challenges rather than structural contradictions. The underlying message was reassuring: the boom is rational, sustainable, and self-correcting.

That framing is less a diagnosis than a performance of confidence. It casts anxiety as a market sentiment that can be measured and managed, converting uncertainty into data. By treating volatility as a sign of health, the bank naturalizes a system that must keep lending, investing, and building even when its foundations are already trembling. The thick veil of economic realism is more of a financial reflex. One must not lose sanity. At least in some part, an institution must believe in the future it is leveraged against.

How banks are manufacturing stability (for now) in the AI bubble economy

Deutsche Bank has lent billions to data-center developers serving clients like Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet, and is now looking to hedge that exposure. It is reportedly shorting a basket of AI-linked stocks, arranging a synthetic risk transfer (a deal where the bank keeps the loans but buys protection on the riskiest slice), and preparing, via its asset-management arm DWS, to sell about €2 billion of its own data-center assets. The aim is not to exit the AI economy but to stay deeply embedded in it while shedding as much downside risk as possible.

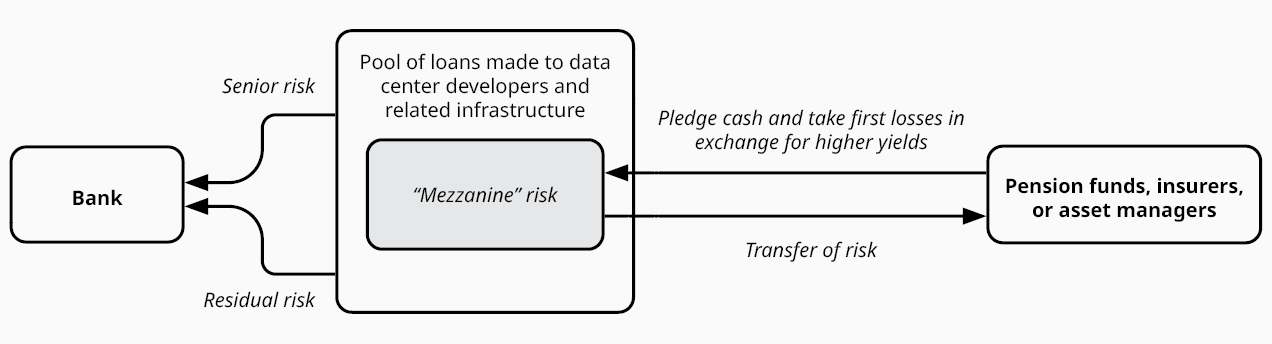

Synthetic risk transfers and securitizations are what really make this balancing act workable. In these deals, investors such as pension funds, insurers, and hedge funds agree to absorb a defined share of potential losses in exchange for yield. Banks shift credit risk into capital markets, freeing space on their balance sheets for new lending while keeping the client relationships, fee income, and appearance of safety. Each new layer of “protection” supports another round of expansion, and many regulators now treat these instruments as ordinary tools for managing capital requirements. Yet the International Monetary Fund estimates estimates that since 2016 more than $1 trillion in assets have been synthetically securitized in this way and warns that data gaps make it difficult to see where that risk ultimately ends up.

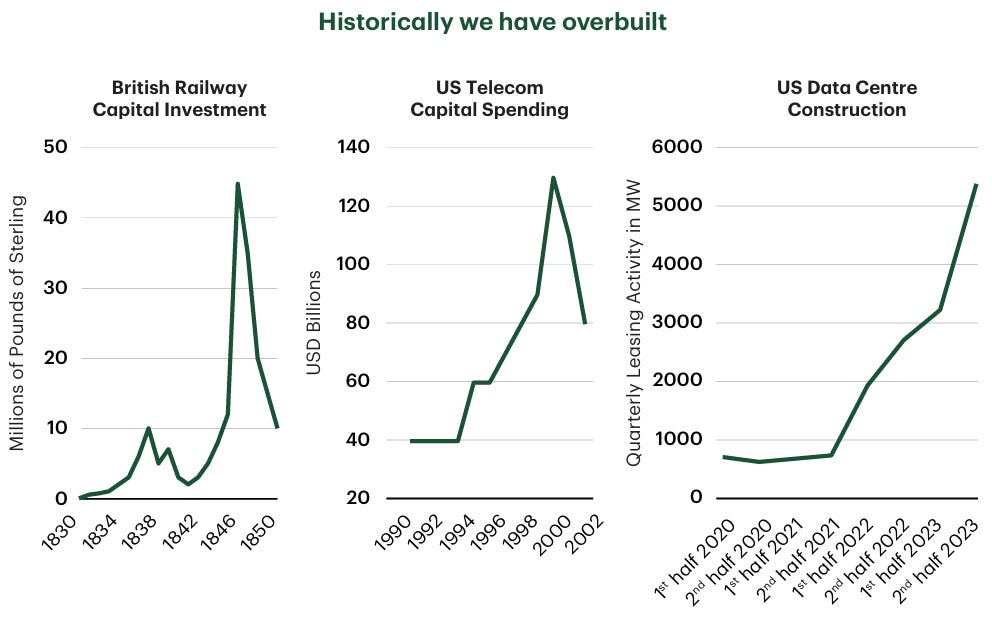

Other banks are moving in the same direction. Germany’s Aareal Bank completed its first €2 billion synthetic risk transfer this year, and UniCredit Bulbank shifted €2.1 billion in loan risk to the Dutch pension manager PGGM. Toronto-Dominion (TD) Bank executed one of the first North American transfers backed by data center exposures. A report by TD likens today’s data center buildout to past railway and telecom booms and describes their crashes as “digestion periods,” a framing that reassures investors by normalizing those downturns while obscuring how losses were actually borne by ordinary savers and workers.

This architecture supports the ongoing build-out of AI infrastructure despite public fears of a bubble. In effect, deals like UniCredit’s with PGGM and Deutsche’s co-lending with the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board pull long-term retirement savings directly into the financing stack that sustains the data center economy. Pension and insurance capital becomes the cushion that lets banks keep lending to increasingly leveraged projects. The Bank of England recently warned that AI-related infrastructure will require trillions in investment over the next five years, much of it financed through debt. At the same time, the same banks funding these projects are quietly exporting their risk to the very institutions meant to safeguard the public’s future.

Risk management for banks means risk exposure for your retirement savings

In market language, this is called efficiency. In political terms, it is displacement. Long-term, capital-intensive assets—data centers, transmission networks, energy contracts—are being converted into streams of tradable exposure. Future rents and power purchase payments are bundled into synthetic securities that promise steady yields to investors who may never see the infrastructure they finance. Land, water, and energy systems are reorganized to serve the requirements of these contracts, with the built environment increasingly shaped by where credit can be placed rather than by what communities need.

I’ve been arguing that the crucial question is where this risk actually ends up. When banks use synthetic risk transfers, the counterparty on the other side of the trade isn’t some speculative day trader. It is more often a pension fund, an insurance company, or a sovereign fund managing retirement savings and public reserves. In other words, the liabilities of the AI build-out are being laid on top of the balance sheets that are supposed to guarantee income in old age. Dutch healthcare workers, Canadian public employees, teachers and civil servants across Europe and North America become indirect backers of AI infrastructure when their pension managers buy into these structures. What looks like a safe, diversified fixed-income allocation may in practice be a thin slice of concentrated risk in a sector whose economics are not yet proven.

This changes who absorbs the shock if AI infrastructure underperforms or is rapidly rendered obsolete. An overbuilt or stranded data center might be written down on a bank’s books, but the first losses will often fall on the pension vehicle that sold protection or bought a subordinated tranche. Banks keep the origination fees, advisory roles, and reputational benefits of financing “innovation,” while the downside is scattered across diffuse pools of retirement capital. Regulatory frameworks treat this as sound practice. Risk has been “transferred,” capital has been “freed,” and the banking system appears more resilient. In reality, the exposure has moved from institutions designed to take credit risk to institutions supposedly designed to provide long-term security—and this isn’t even getting into the risks of 401(k)s.

The reassuring narratives of the AI bubble leave all of this out. The real issue is not whether an AI bubble can be statistically proven, but how its continuation is being underwritten by people who never chose to invest in it. By fixating on search trends and investor sentiment, Deutsche Bank’s report turns a structural question about who funds and who absorbs the costs of AI infrastructure into a passing question of market mood. In reality, the tools of risk management are being used to extend a speculative cycle, with pension funds, retirement systems, and quite possibly taxpayers acting as the backstop. And if what follows the boom is politely described as a “digestion period,” we should be clear about whose futures are being chewed up and broken down in that vat of speculative volatility.

To call this “structural violence” is to name this transfer of risk accurately. The AI boom proceeds as a project of accumulation secured in part by the same savings that should protect people from insecurity. Banks present their hedging and capital relief as prudence, and for a small, wealthy slice of the system, it is. But for those whose retirement savings sit behind these trades, prudence looks a little different. It would mean not having their retirement tied to the fate of data centers they will never see, in places they will never visit, built to service a technological frontier whose winners are already well insulated from loss.

See related articles:

Great analyses! Thanks for raising this financial perspective on the infrastructure buildup